A Complete Unknown

Director James Mangold

A beautiful work of art about art. An absolutely beautiful film in every way.

Michael Walsh, Nerdist

Index

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Bleecker & MacDougal Street

- Chapter 2: Bob Dylan’s Apartment

- Chapter 3: Gerde's Folk City

- Chapter 4: Greystone Hospital

- Chapter 5: Revival Movie Theater Street

- Chapter 6: Seeger Cabin

- Chapter 7: Columbia Records

- Chapter 8: Chelsea Hotel

- Chapter 9: Viking Motel

- Chapter 10: Monterey & Newport Folk Festivals

Read the full article

in perspective magazine

“How does it feel?” This query posed by 24-year-old Bob Dylan became my guiding mantra for the design of James Mangold’s film “A Complete Unknown.” Beyond historical accuracy; I sought to capture the essence, the feeling of the early 1960s.

What did it feel like to walk the cobblestone streets of Greenwich Village, to sit in a smoky coffeehouse listening to a beatnik poet, or to experience the tension of a society on the brink of transformation?

The 1960s ushered in an era of profound musical and cultural revolution. Melodies evolved from carefree jingles to complex narratives, carrying powerful social messages. At the heart of this movement was Bob Dylan, a name now enshrined in history. The film traces the journey of a 19-year-old songwriter as he arrives in New York City, seeking to find his hero, an ailing Woody Guthrie.

The narrative unfolds as Dylan immerses himself in the vibrant New York folk scene, mingling with luminaries like Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Joan Baez. The film captures his ascent from being a complete unknown to becoming a cultural icon.

the ballad

of a true original

It also delves into the complexities of his relationships—both with his lovers and standouts in the folk music community—and his eventual departure from these connections. The film also portrays his transition from folk to rock, a move that both electrified and perplexed his audience—some feeling bewildered and betrayed.

During my research, I found that Dylan’s earlier career was well documented, but this wealth of research also created a challenge as it placed a very high bar for authenticity. I directed my team to look beyond the visual references and attempt to conjure the spirit of a time when music was a vehicle for social change, where every street corner, neighborhood bar, and dingy apartment was a breeding ground for revolutionary ideas. By immersing the audience in the tactile, sensory-rich world of early 1960s Greenwich Village, I hoped to make them not just see, but feel the profound impact of Dylan’s journey from obscurity to legend.

In early discussions with Mangold—back in February 2020—the real Bob Dylan reminded him that the early 1960s still looked like the late 1950s. The 60s we imagine—with vibrant colors and loud fashions—didn’t occur until the cultural explosion of the mid-1960s. Our story took place during the early 1960s, a transitional period in American culture. It was then, as Dylan prophesied when he sang “the times they were a-changin’. And they were changing most rapidly in cultural epicenters like Greenwich Village on the East Coast and the Bay Area on the West Coast. I imagined these centers were Petri dishes with spores of culture—art, poetry, music—feeding off each other and bubbling out of the confines of those dishes, oozing inwards from the edges of America.

The heart of this story is about a young artist arriving at the right place at the right time. As I did more research, I theorized that the setting was as much responsible for Dylan’s success as Dylan’s own talents. There was a symbiotic relationship with Dylan, in which the place made the man, and the man-made the place.

But what made the Village, the Village? For me, it was the mix of artists living closely together within a small footprint. Folk singers, poets, painters, beatniks, and jazz musicians all sharing the same space. With low rents, they could afford apartments, coffee shops, and studios. This rich, layered visual tapestry of the Village was essential to our storytelling.

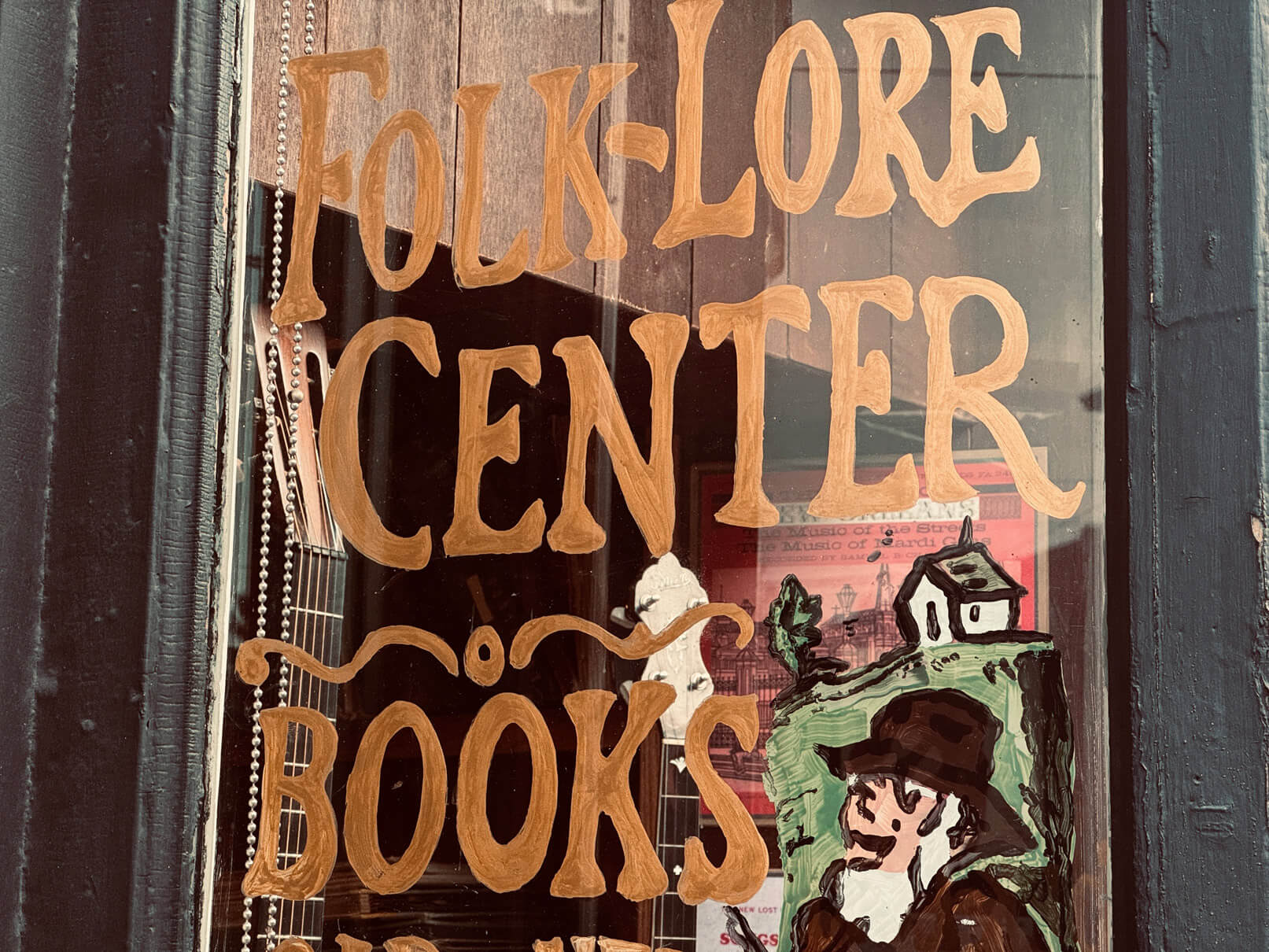

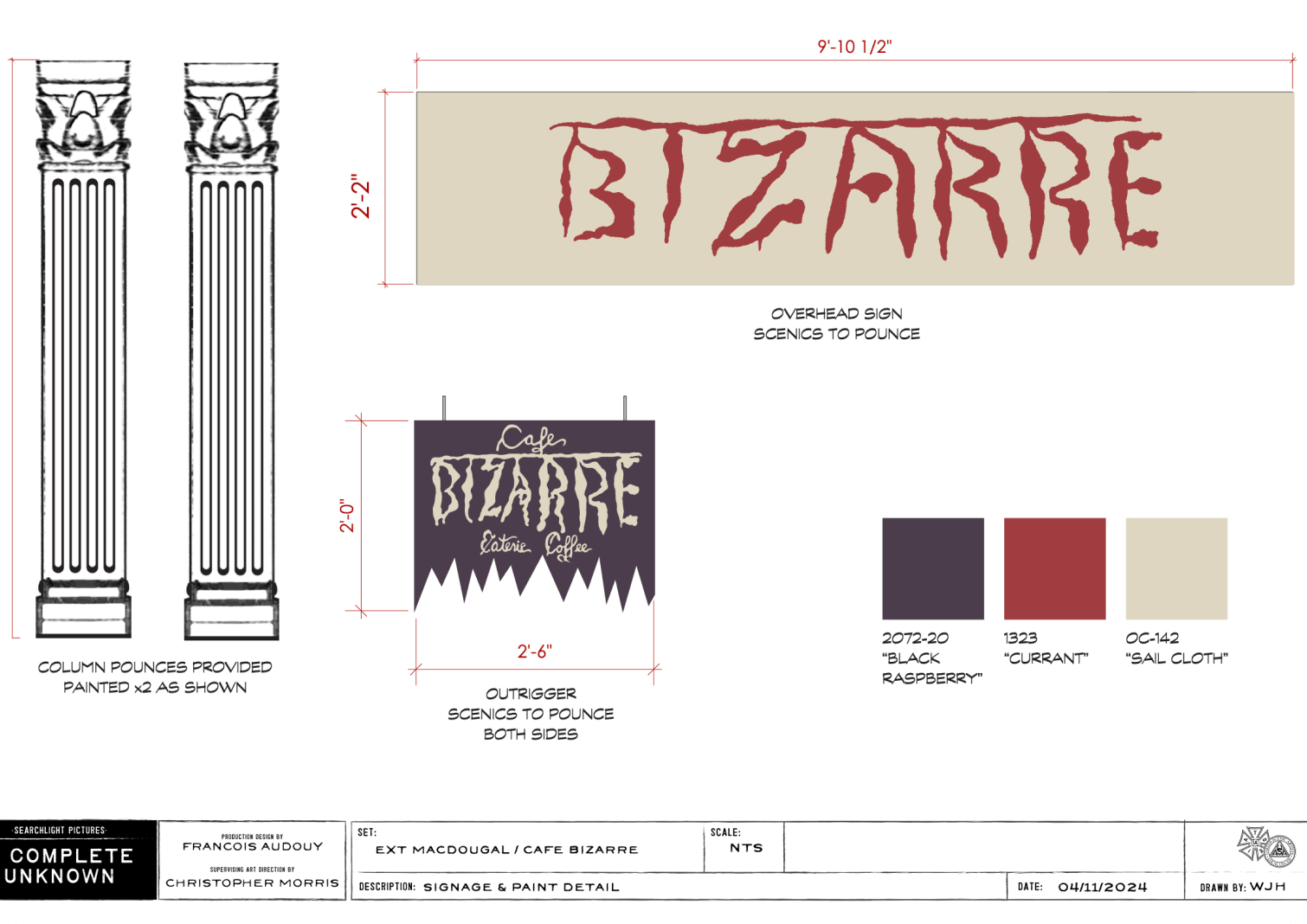

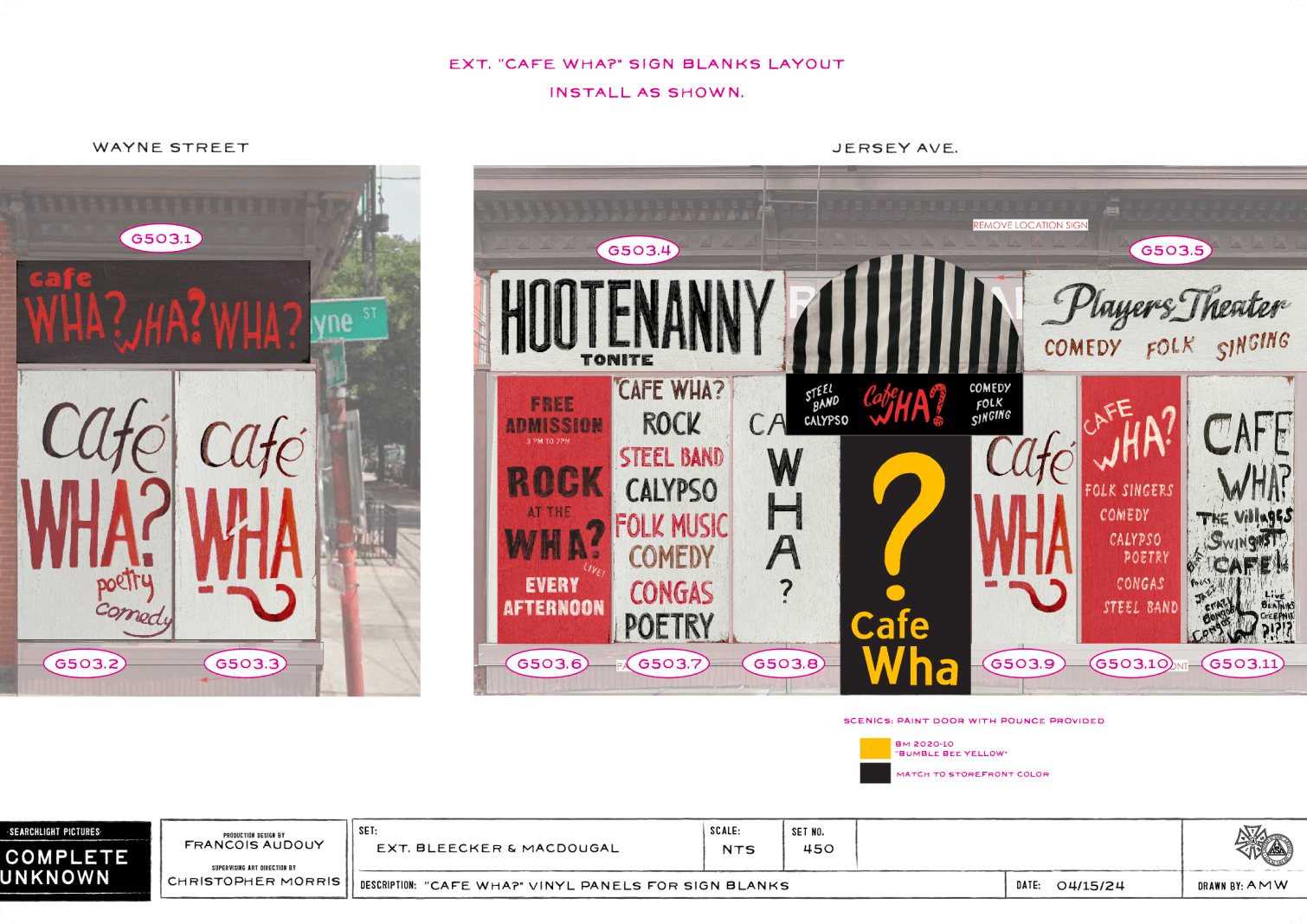

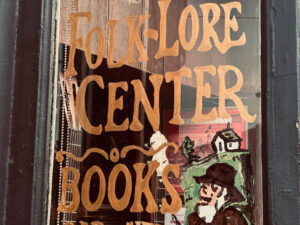

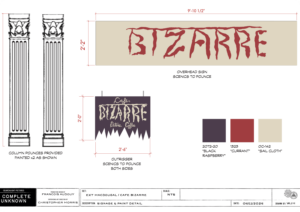

Inspired by this art scene, I took a humanist approach to the production design, meaning that I decided all the scenery would highlight hand-made craftsmanship. I mandated we forgo digital production techniques whenever possible and lean into old-school crafts, like hand-painted signage, sets built using hand tools, and scenic painting with as much character and age as possible. I wanted to see brush strokes and all the rough edges of this world.

In terms of color, I was particularly inspired by the New York Kodachrome photography of Saul Leiter, Ernst Haas, and Tod Papageorge, and shared their images with Cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, as well as my scenic team. Using these many visual references, I worked closely with Concept Illustrator Kristian Llana to influence the lighting of the sets, who explored various lighting scenarios in Blender 3D.

Chapter1

Location

Bleecker &

MacDougal Street

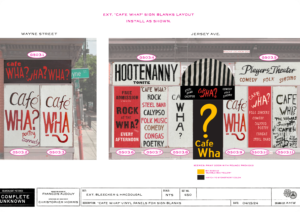

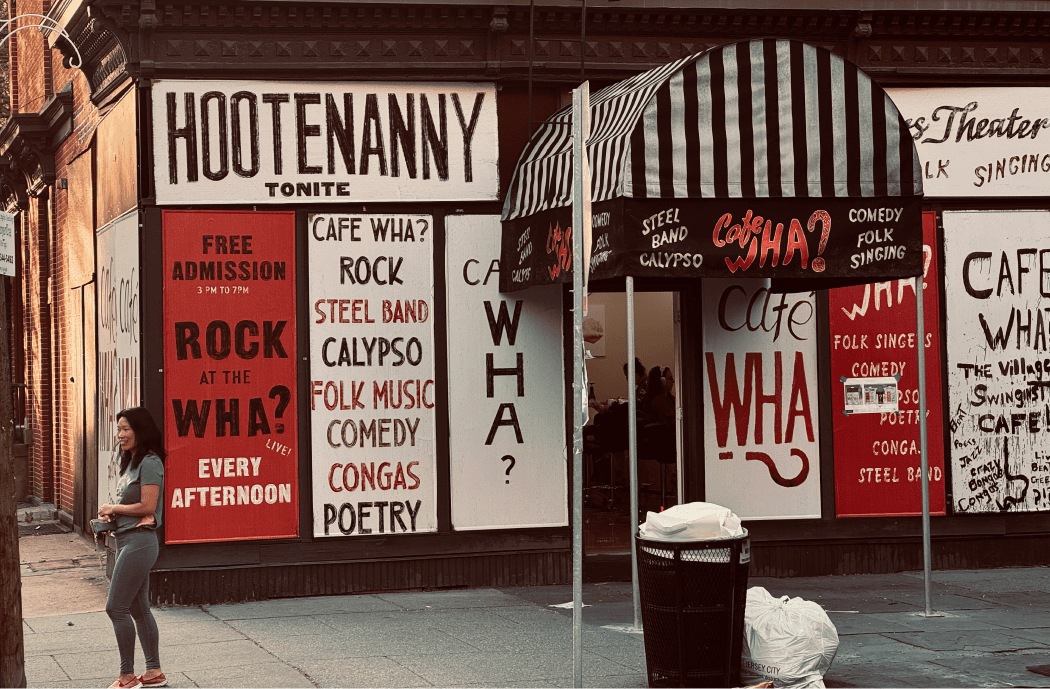

Iconic spots like Cafe Reggio, Cafe Wha and the Gaslight Cafe were all faithfully recreated, along with the neighboring jazz clubs like Swing Rendezvous and restaurants such as Minetta Tavern and the Kettle of Fish. (Admittedly a bit obsessed with the period details, I insisted on matching the paint colors of the still-operating Cafe Reggio in NYC) In the heart of MacDougal street, we also recreated the Folklore Center which was a shrine, of sorts, to all things folk.

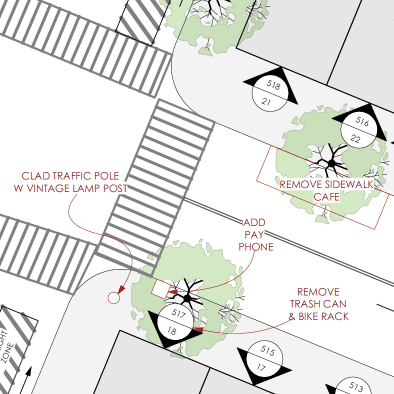

We transformed two blocks in Jersey City to recreate Dylan’s MacDougal Street haunts, complete with coffee shops, bars, liquor stores and art galleries.

The task involved reproducing original signage and storefronts, but more importantly, capturing the atmosphere of the “jingle jangle mornings” Dylan described in “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

1960’s Greenwich Village has a very eclectic look. It’s the intersection of classic New York neon, hand-painted Mom & Pop shops, and the energetic freeform design of bohemian downtown,” said Graphic Designer Will Hopper.

“Historical research was crucial to re-creating graphics of the period accurately. Many of the storefronts which appear in the film are true-to-life. Our 4-person graphics department spent time redrawing unique fonts and MacDougal Street signage. We fabricated these pieces through a mixture of digital and scenic painting. Macdougal Street alone entailed a re-creation of 18 shopfronts and venues,” Hopper added.

“This film sweeps you up in its beautifully detailed vision of an analog New York where stars eat at greasy spoons below 14th and future music legends pass the hat in basement clubs. Scrounging for their next meal.”

John Oleksinski

New York Post

Gallery

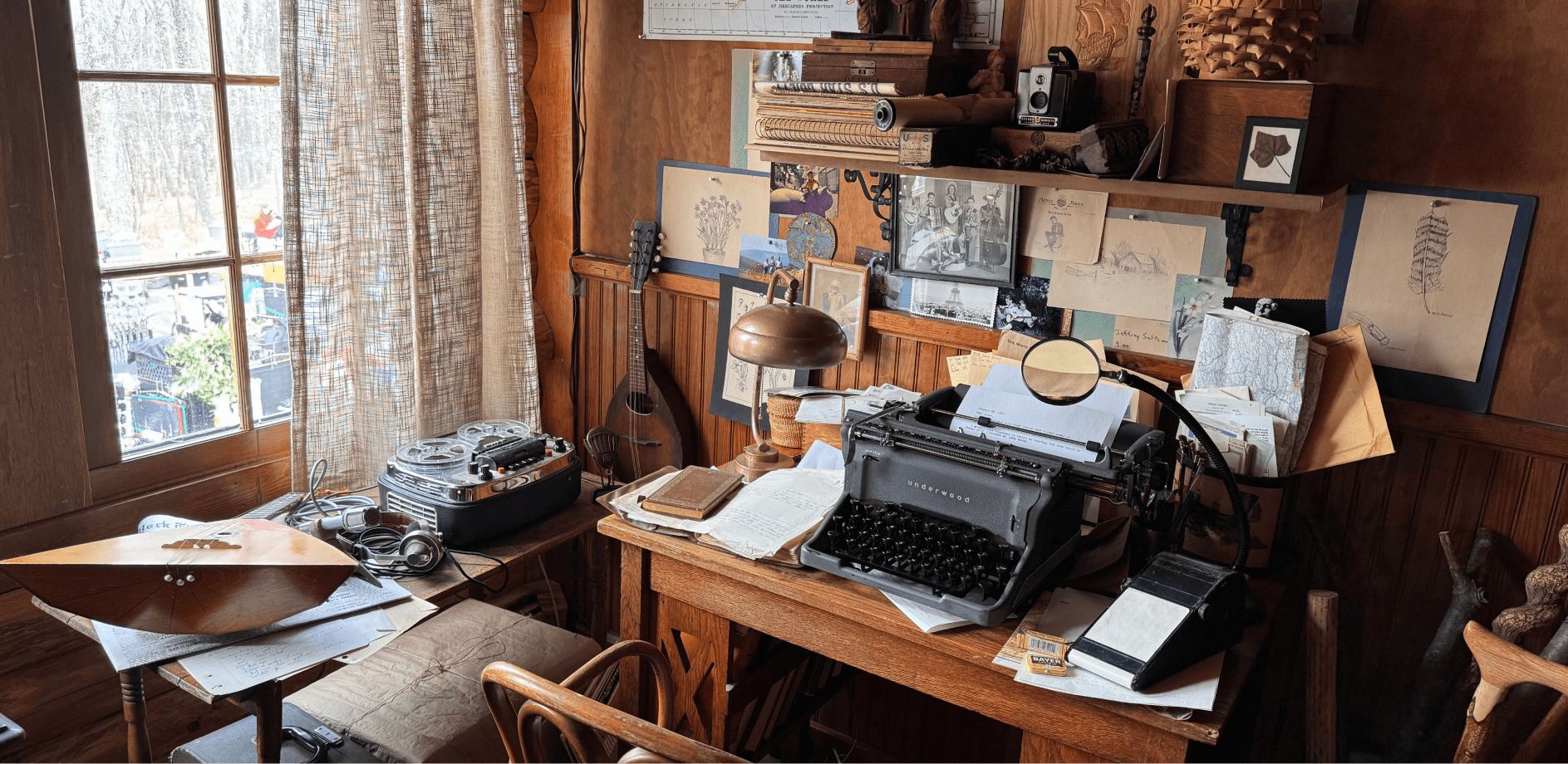

Chapter2

location & Set Build

Bob Dylan’s

Apartment

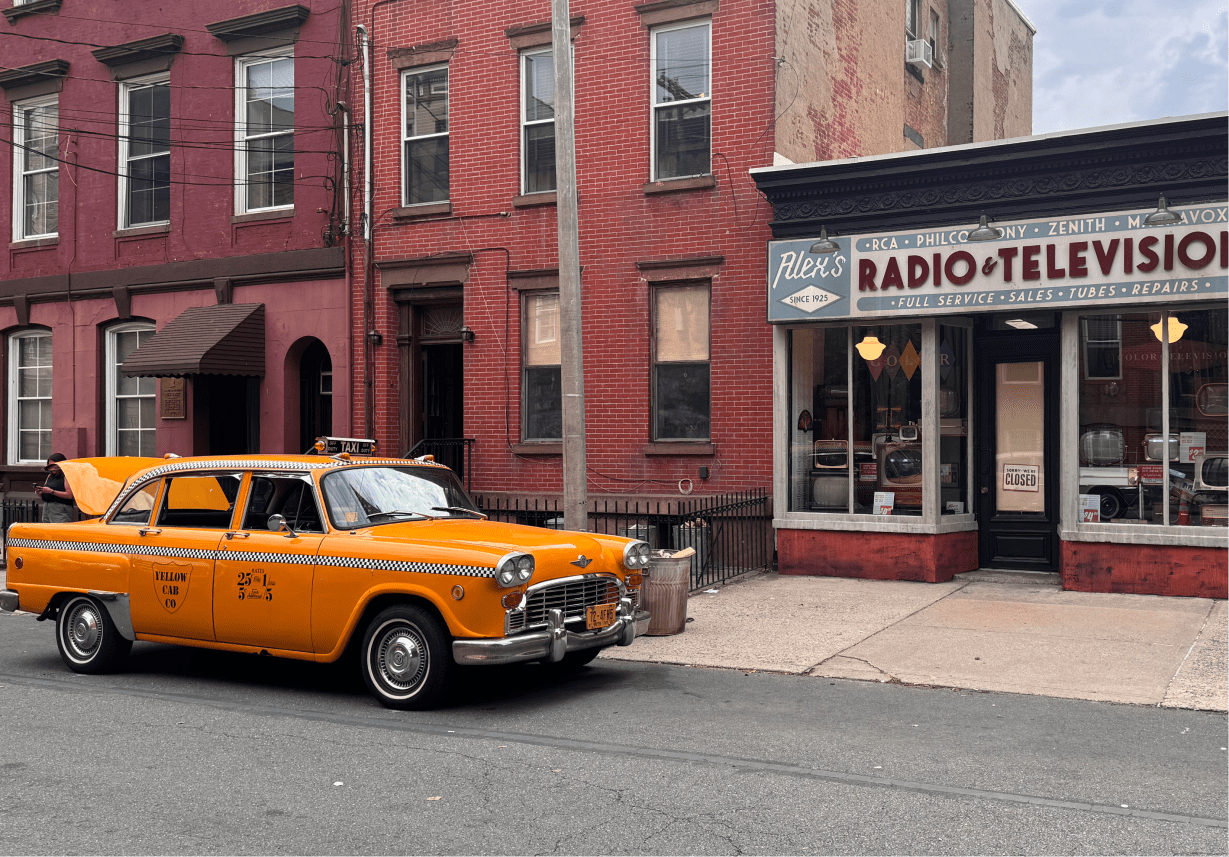

The exterior of Dylan’s Fourth Street apartment and an adjacent television repair shop were filmed in Hoboken. We dressed an entire building with six apartments for a scene where Dylan espies his neighbors all watching President Kennedy’s televised 1962 “Cuban Missile Crisis address.” The setup evoked the atmosphere of James Stewart’s view of his neighbors in Hitchcock’s “Rear Window.”

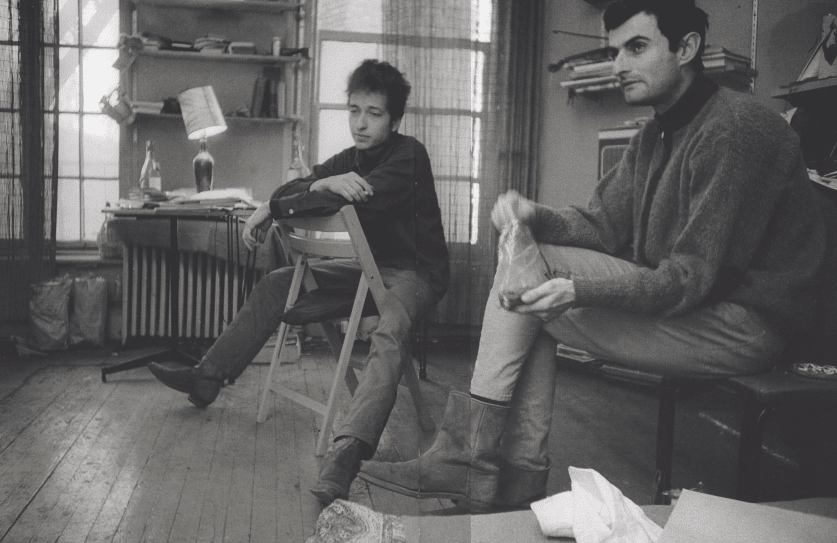

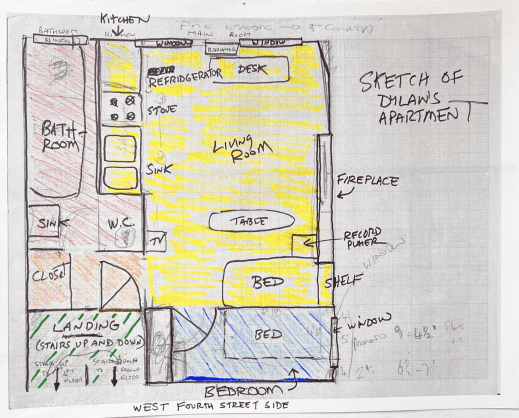

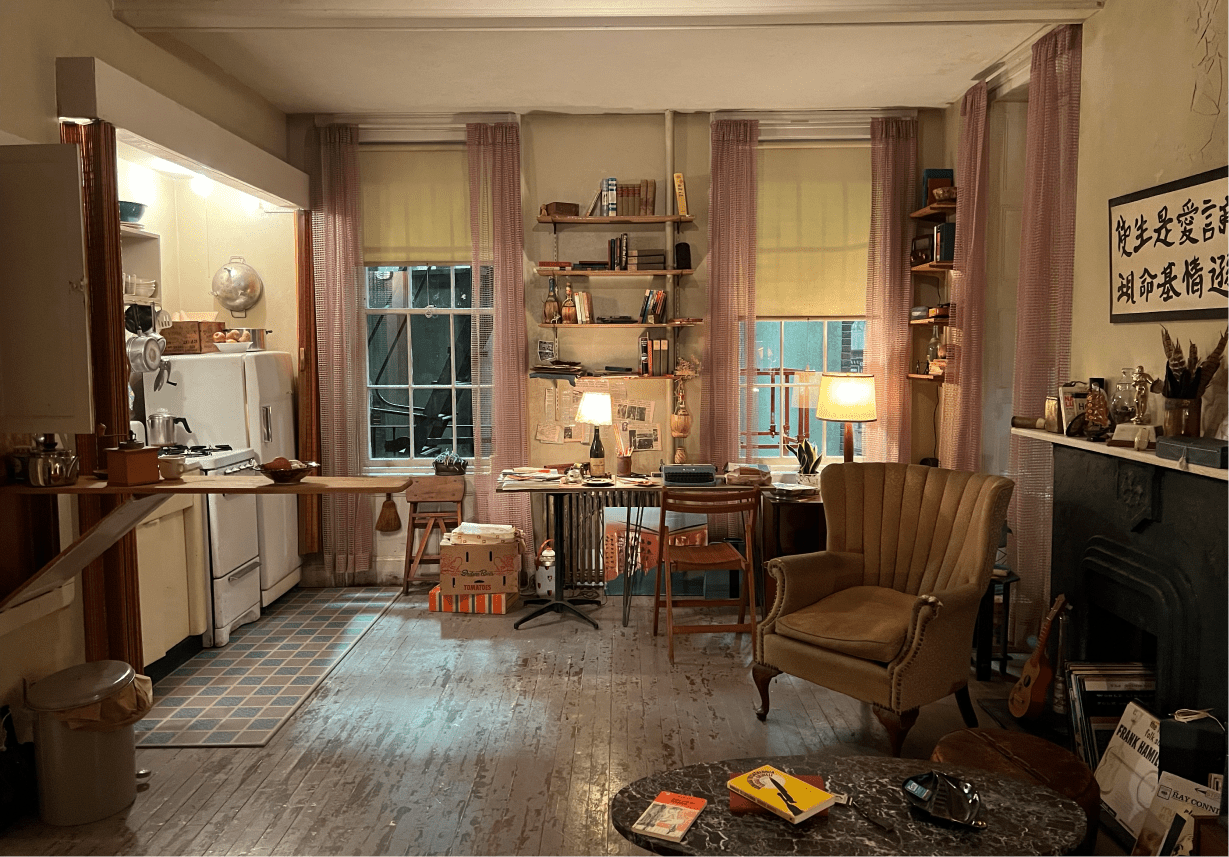

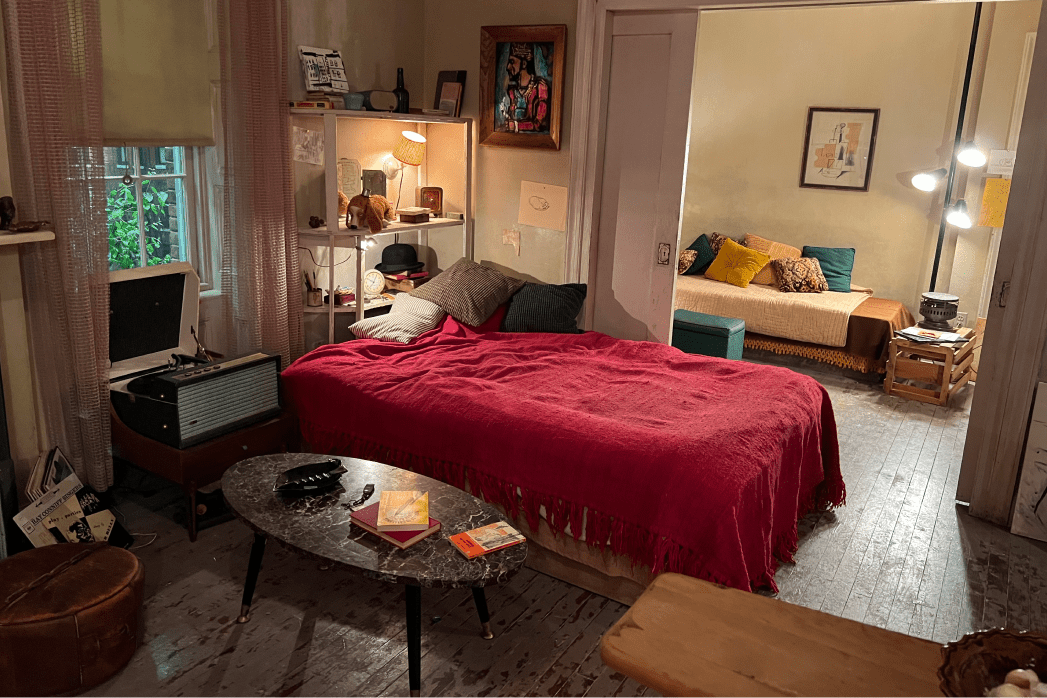

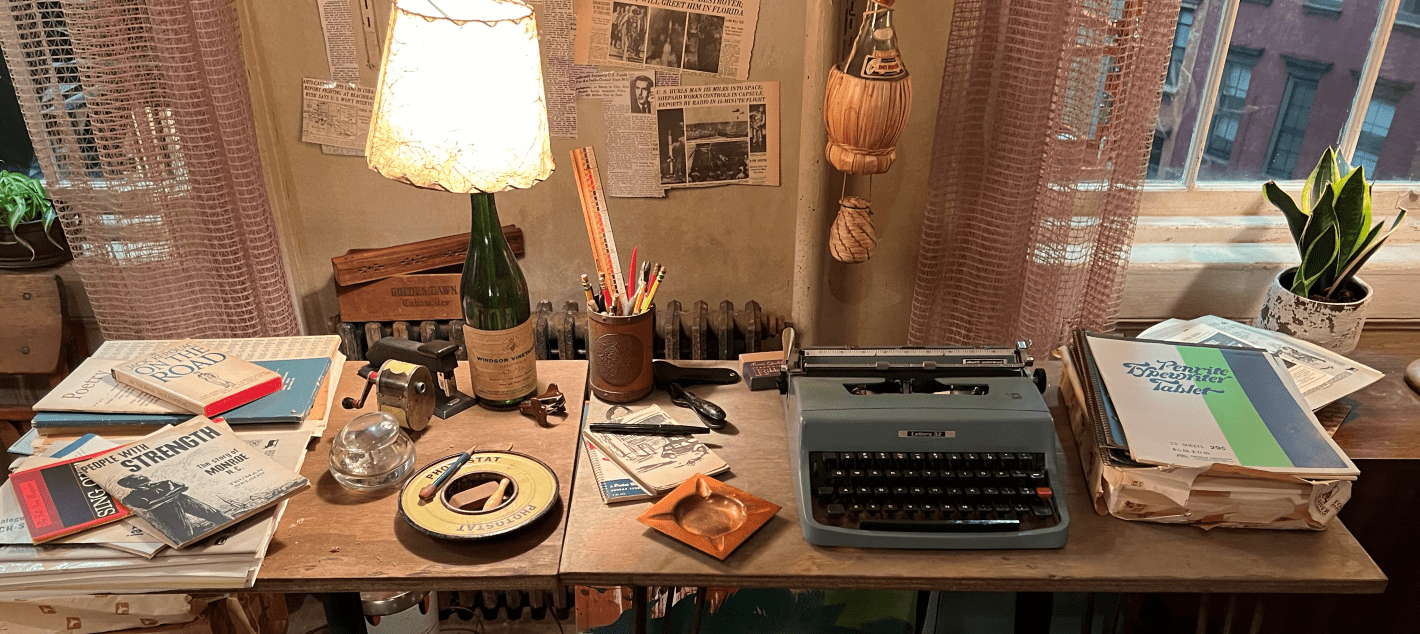

The interior of Dylan’s apartment—where he lived from 1961 to 1964—was constructed as a stage set to accommodate five days of filming.

Using scans of about 200 of Photojournalist Ted Russell’s original negatives, we meticulously recreated every minute detail, from Dylan’s furniture and record player (a 1950s Decca) to his typewriter (an Olivetti Lettera 22), books, artworks, his bathtub and even his stuffed plush toy (an adorable wiener dog).

The set was fully immersive and interactive with plumbed faucets, a working stove, and electricity. All the details, like news clippings on the wall, Dylan’s albums and books, were all carefully designed to hold up to potential closeups.

The set featured layers of painted texture on the plaster walls, adding to the authenticity. The narrow stairway leading to his unit was painted in colors scanned from 1950s paint swatches, Set dec tiled the bathroom in New York subway tile, chipped away and broken from disrepair.

A hardwood floor was installed, stained and then overpainted with a gray deck paint often used by landlords and tenants alike in old buildings to make the floors look better.

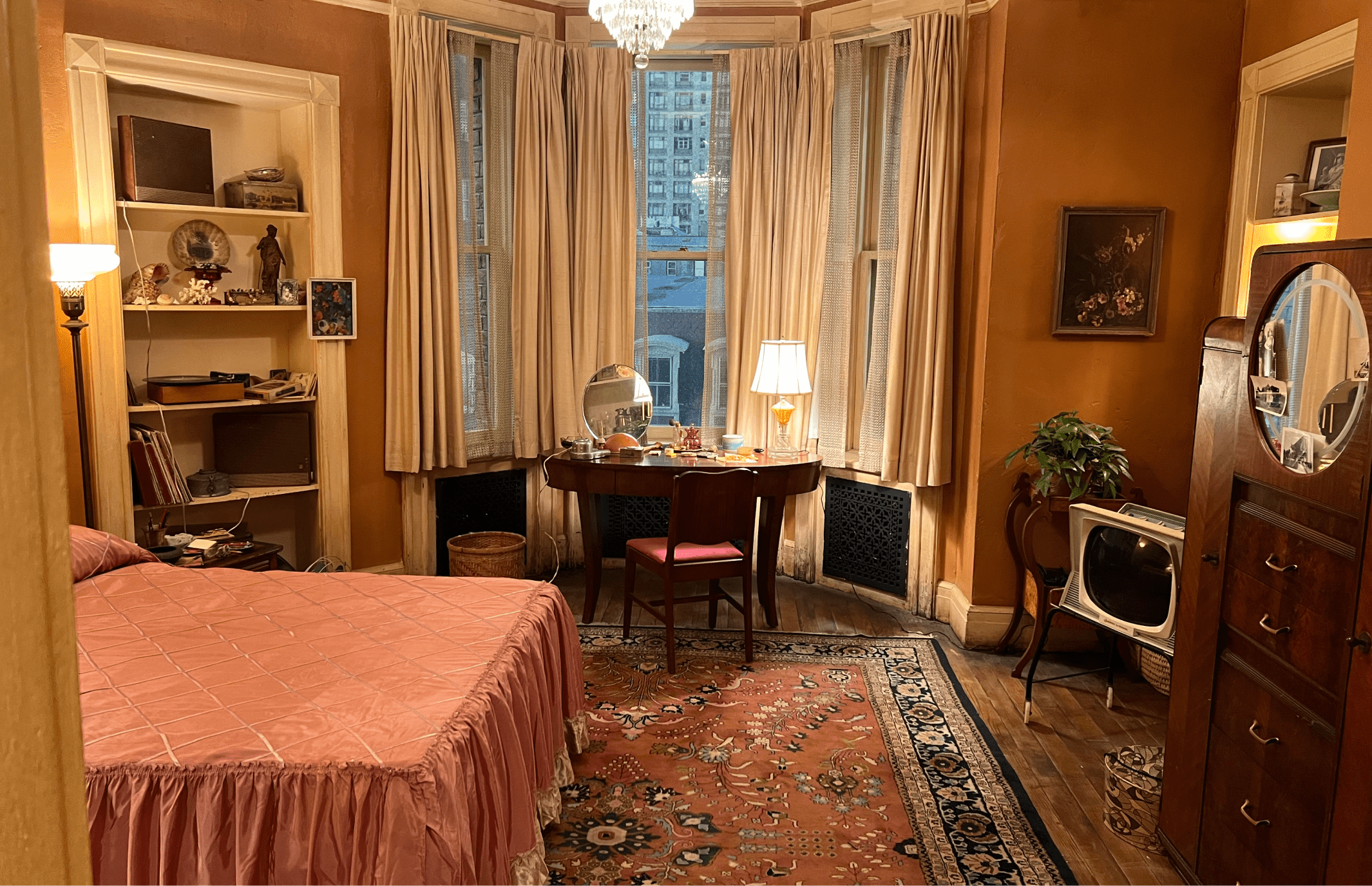

“Audouy’s sets are packed with the layered detail of a pre-gentrification hipster neighborhood, notably Dylan’s messy 4th Street apartment and, a little further uptown, Baez’s boho-chic room at the Chelsea Hotel.”

David Rooney

The Hollywood Reporter

A backing by Roscoe Digital Imaging was captured at the exterior location (where we also shot looking out from that interior location which matched the stage set). It was then digitally manipulated to reflect the accurate 1960s New York skyline.

In the stairway leading to Dylan’s front door, we purchased actual salvage antique stair spindles which turned into a reference for our scenic artists to match the surrounding peeling paint to.

“Dylan’s chair was a particularly hard one to source,” admitted Regina Graves. “We were finding so many vintage wing chairs, but this one was so specific because of the channel back, the gold pattern, the studded arms , and the Cabriole leg. After an exhausting search and when our go to sources left us empty handed we ended up finding the perfect one on Amazon Marketplace. It was from the home of the seller’s grandparents.

“The other smalls and furnishing for the apartment were sourced in antique and thrift stores across New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania.”

Chapter3

Location

Gerde’s

Folk City

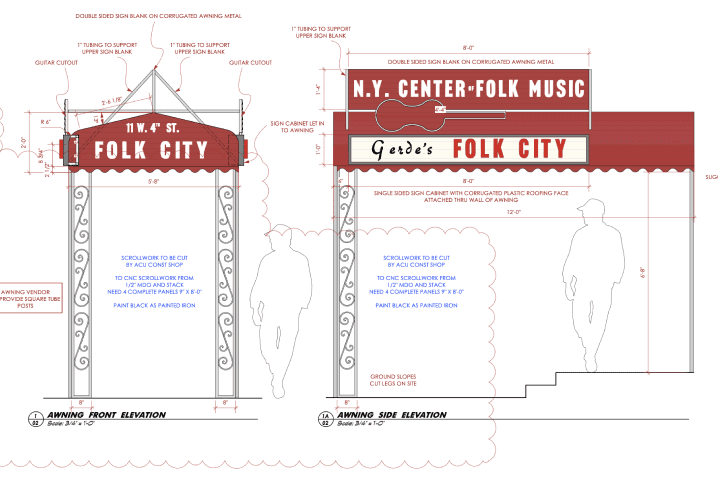

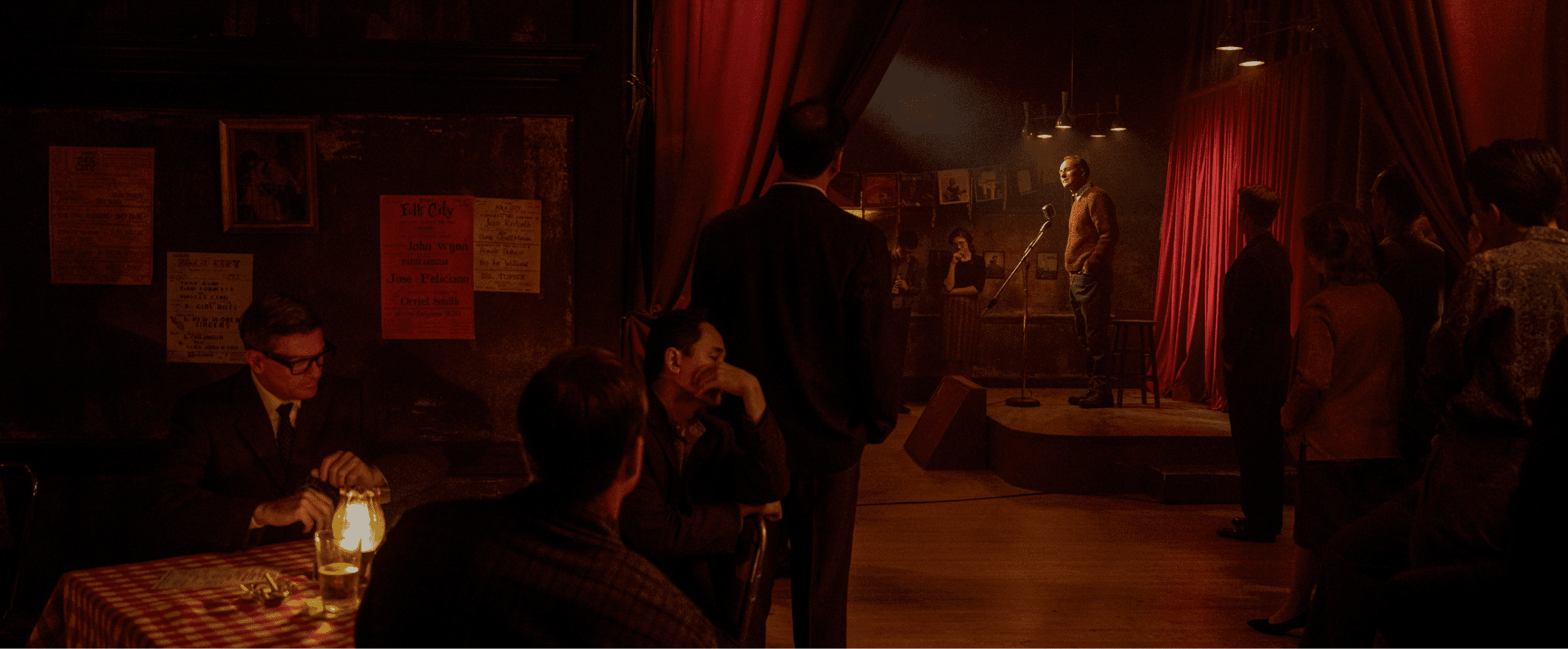

Gerde’s Folk City was probably the most important folk-music venue in New York City at the time—the club that every folk act with a national profile played when they were in town.

It was important to capture authentically, as it was in this storied club that Dylan played his first major gig in 1961.

To create this space, we took over the historic Elks Lodge #74 in Hoboken and transformed it by painting the space in dark, sultry tones with Havanaesque plaster. The downstairs bar doubled as a second location—the Gaslight Cafe—replete with a staircase descending from MacDougal Street.

The stage’s red velvet backdrop — a striking accent — balanced red and white checkered tablecloths that spoke the the space’s prior life as an Italian restaurant. An old upright piano and framed 8×10 photos of folk acts helped create the quintessential folk club atmosphere.

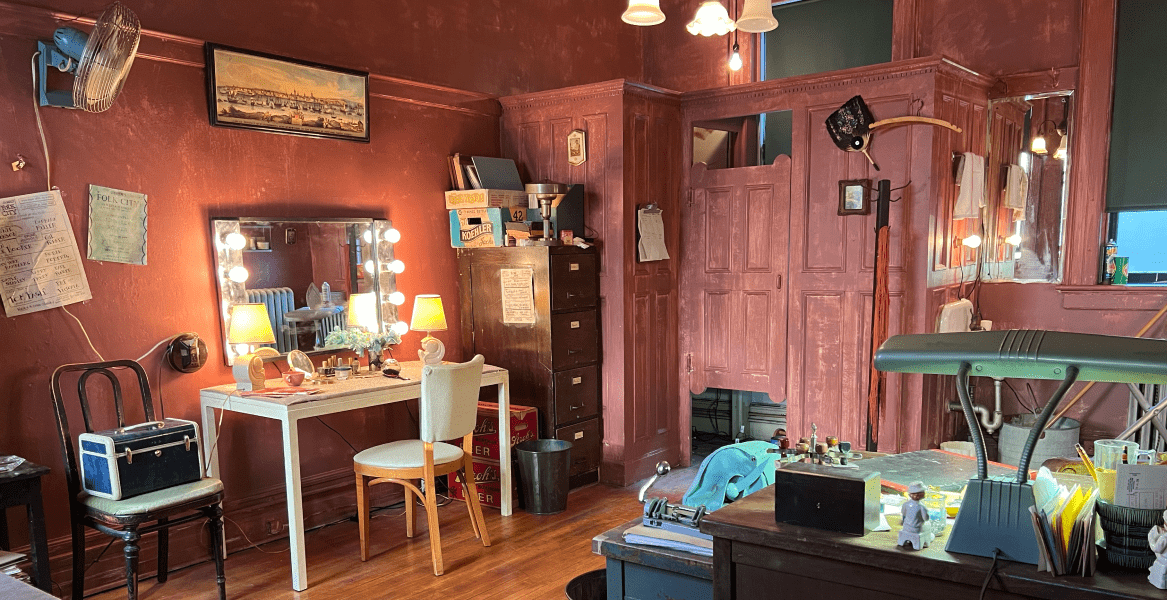

Behind the stage (but actually cheated in a room on the third floor of the location), we imagined Joan Baez’s cramped dressing room. The space featured a salvaged vanity mirror framed by bare bulbs, decaying plaster walls and vintage concert posters.

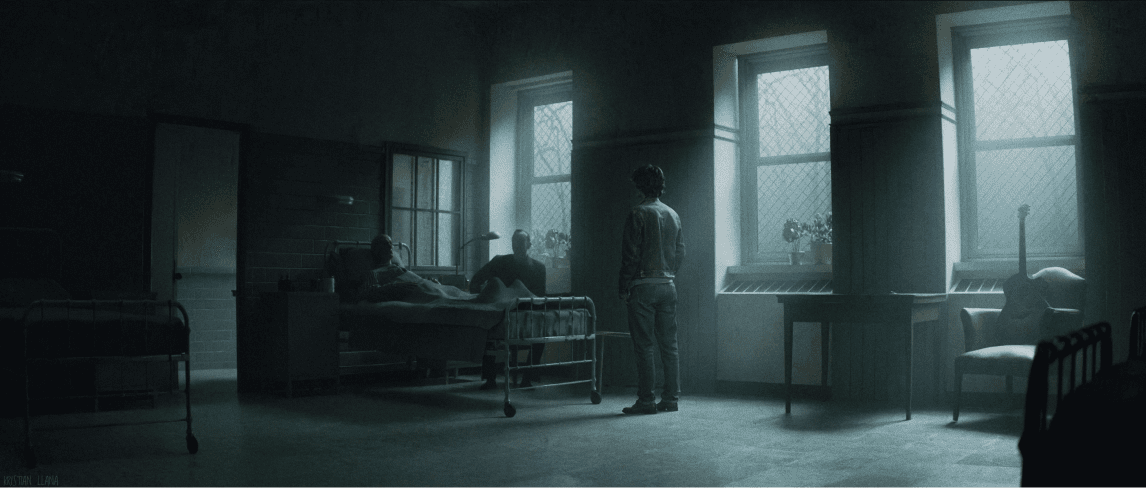

Chapter4

Location

Greystone

Hospital

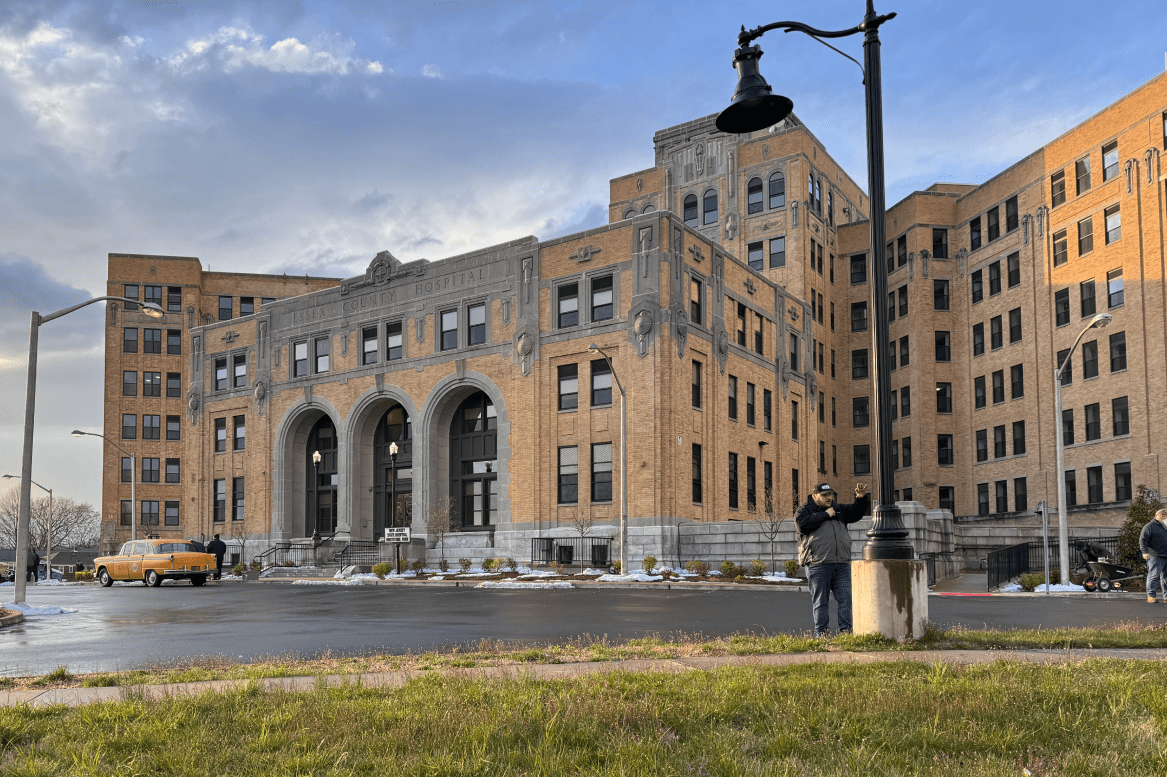

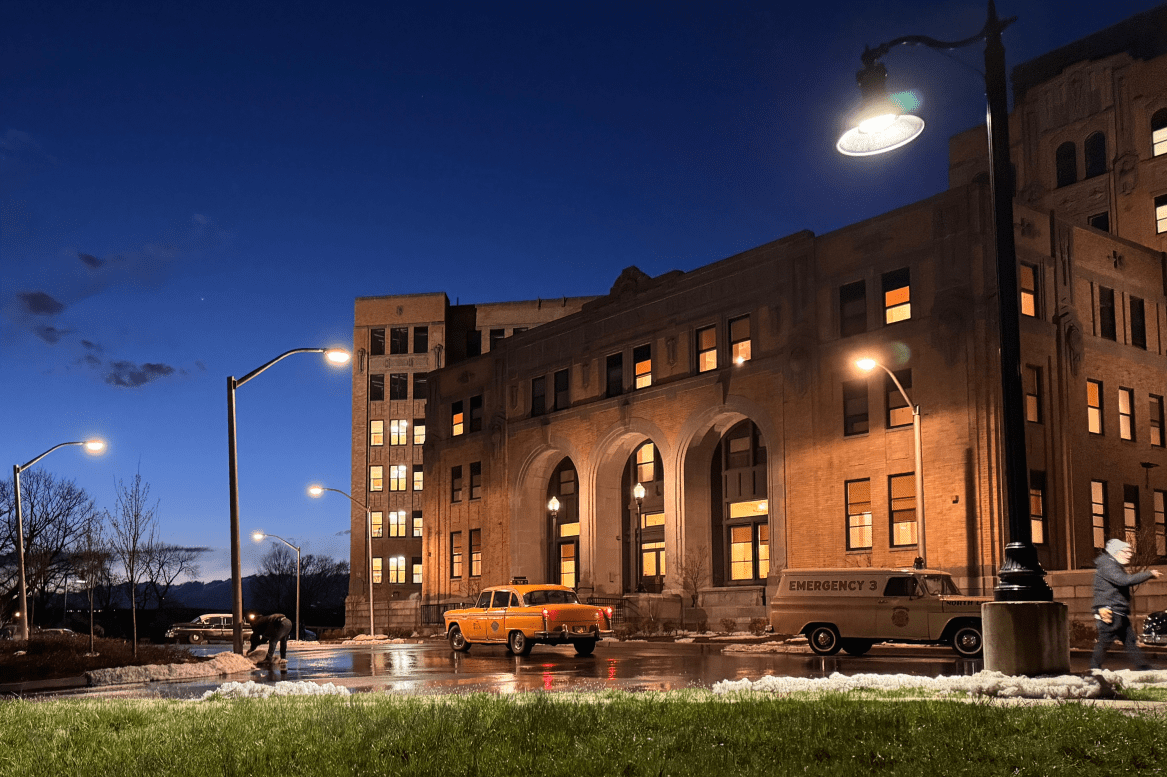

For Dylan’s visit to his hero Woody Guthrie at Greystone Hospital, the imposing exterior of the empty Essex County Hospital felt ideal.

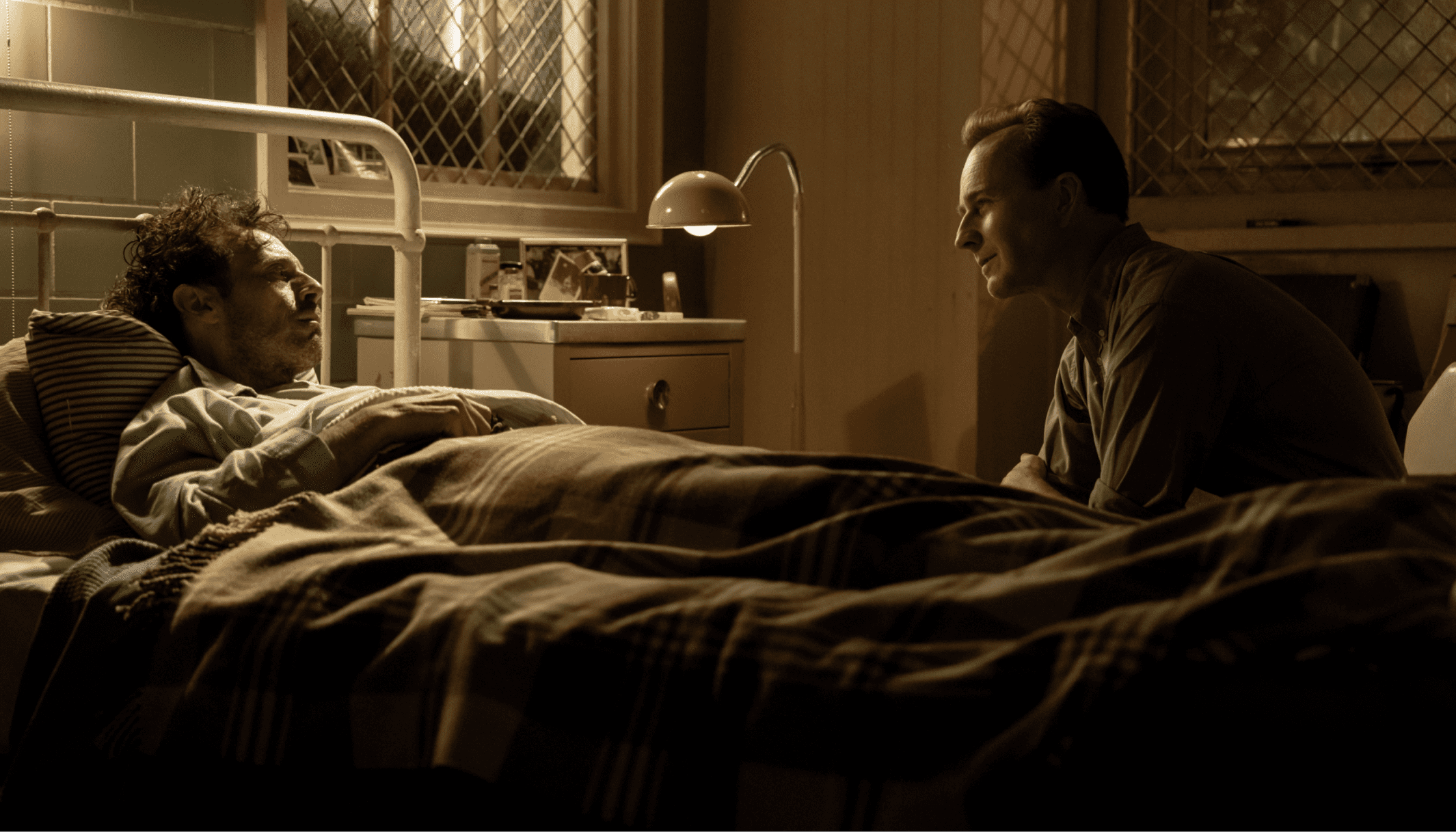

The interior was filmed in a shuttered school near Newark, where we painted hallways and built Guthrie’s room.

Our scenic team expertly extended the location’s glazed tile walls, blending seamlessly with our modifications to recreate the institutional feel of the original, which had been demolished years ago.

We built Woody’s room into a larger space at the end of a long hall, extending the institutional subway tile from the connected hallway. A bathroom was built behind Woody’s bed for added depth in the closeups.

Concept Illustrator Kristian Llana’s concept illustrations captured the haunting institutional atmosphere, particularly the diamond-pattern security grilles across the windows. The period hospital bed and stark lighting created a somber mood that echoed archival photographs of mental institutions of the time.

“I’m out here a thousand miles from my home. Walkin’ a road other men have gone down. I’m seein’ your world of people and things. Your paupers and peasants and princes and kings.”

Bob Dylan

“Song for Woody”

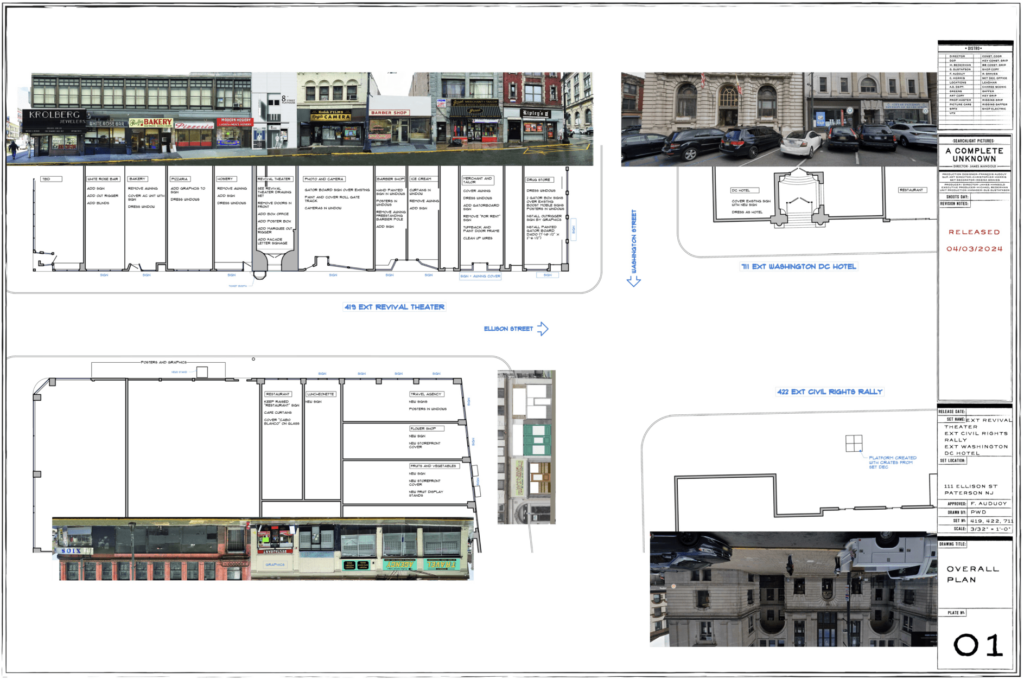

Chapter5

Location

Revival Movie

Theater Street

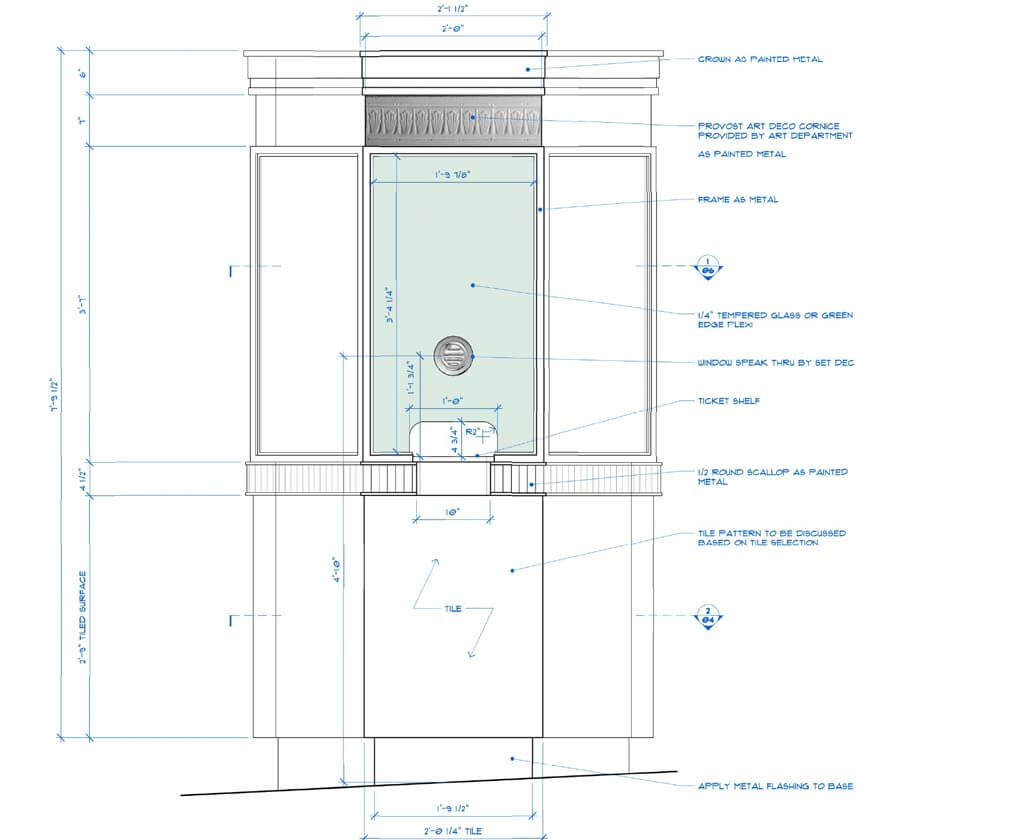

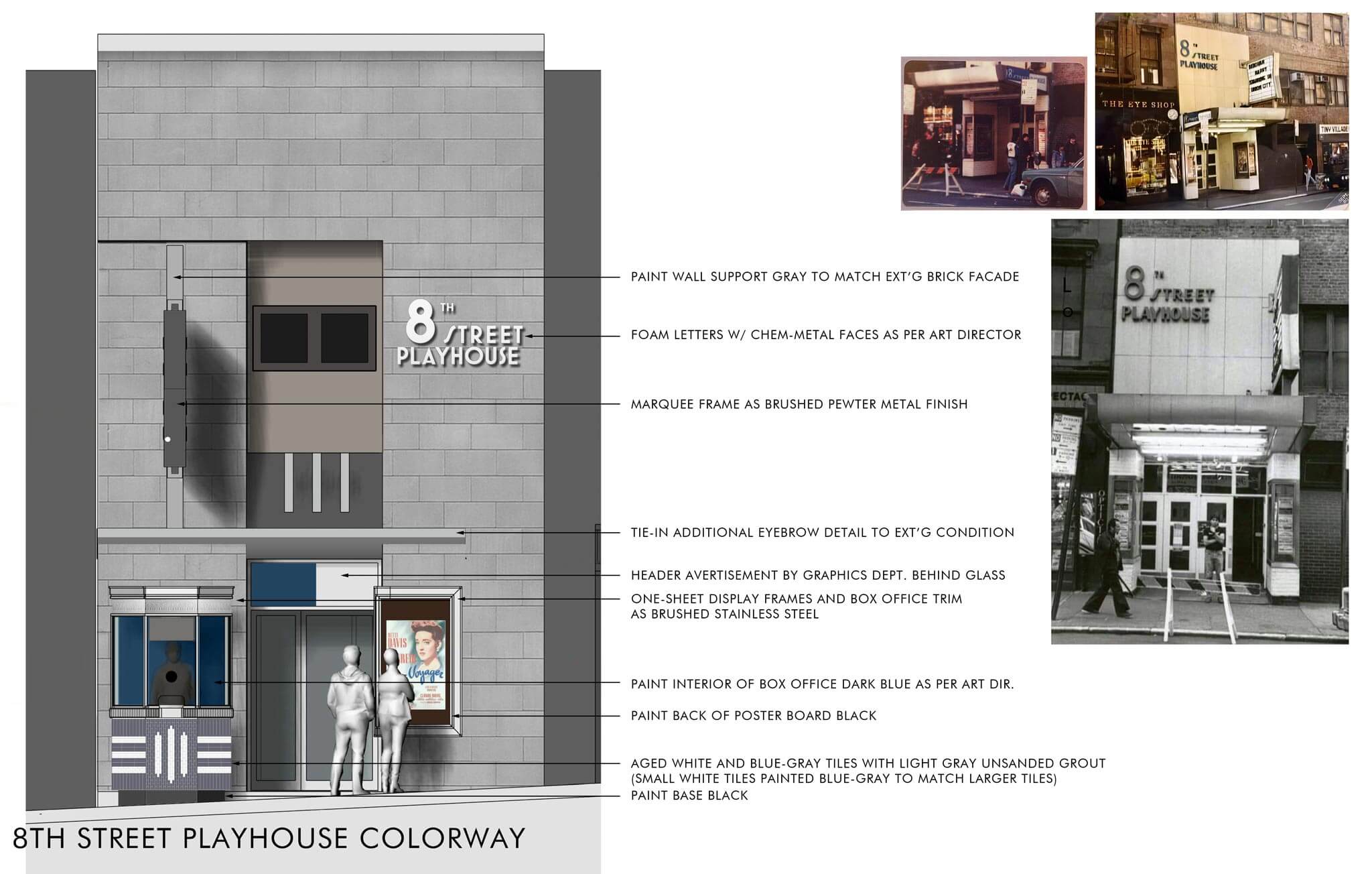

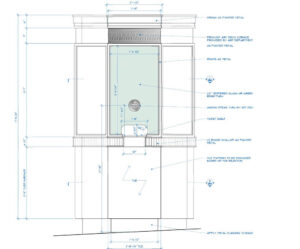

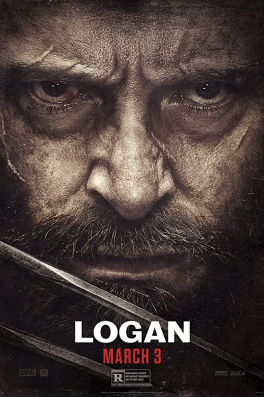

We leaned into a wonderfully preserved block in Paterson and transformed about two dozen storefronts into various businesses. For a “walk and talk” culminating at a revival theater showing “Now, Voyager,” I convinced Mangold to recreate a theater modelled after the 8th Avenue Playhouse, a former neighborhood movie house in Greenwich Village.

The set dressers installed a large custom marquee onto our hero facade, which was a challenge given Paterson’s narrow sidewalks and sloped streets. Additionally, they weren’t allowed to drill into the facade, so the entire structure had to be suspended from a rock-and-roll truss extending from a window above.

Detailed renderings helped us visualize the theater’s Art Deco facade, complete with streamlined aluminum trim and period-correct poster cases.

“Our Village streets built on location in Paterson required 16 shopfronts, which we pulled off in less than two weeks!” proclaimed Graphic Designer Will Hopper. “Much of this was accomplished in a short schedule, from concept to fabrication and then installation.”

Layer upon layer of detail was added to recreate the long-lost world, including period-correct trash littered on the sidewalks as a final touch.

Gallery

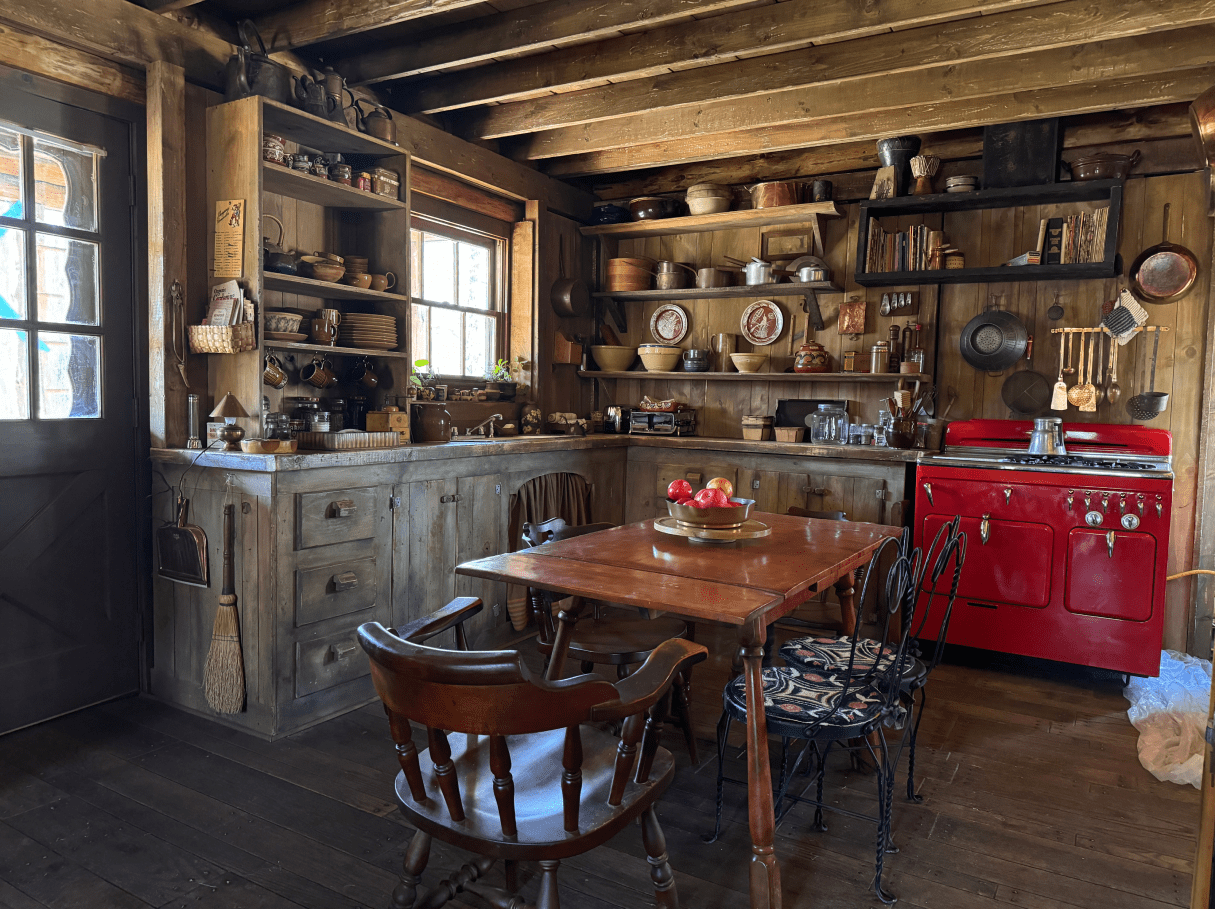

Chapter6

Location

Seeger

Cabin

The kitchen, designed to appear handcrafted by the Seegers themselves, was installed over existing cabinets. A restored 1950s stove was rented for the space, and I opted to cook a bolognese sauce in it the day before the shoot, infusing the set with the comforting smell of a lived-in home.

Pete Seeger’s modest, hand-built cabin was discovered near the Pennsylvania border and became a cornerstone of the film’s authenticity. Edward Norton, cast as Seeger, contributed significantly to our research by visiting the real cabin and interviewing Seeger’s daughter.

His commitment to accuracy inspired me to amp-up the attention to detail, including labor-intensive chinking between the logs and sourcing the same “Freedom Red” appliances the Seegers used. This bold use of red, I dubbed “Kodachrome red,” became a recurring accent color throughout the film.

“Any darn fool can make something complex; it takes a genius to make something simple.”

Pete Seeger

The cabin’s interior reflected Seeger’s folk sensibilities and worldly travels, featuring handwoven textiles, handcrafted furniture, and personal touches like period-appropriate copies of Sing Out! and Broadside magazines scattered across rough-hewn tables. His collection of banjos and exotic instruments, hung from wooden pegs, added layers of character and backstory to the space.

“If you’re traveling in the north country fair

Where the winds hit heavy on the borderline

Remember me to one who lives there

For she once was a true love of mine”

Bob Dylan

“Girl From North Country”

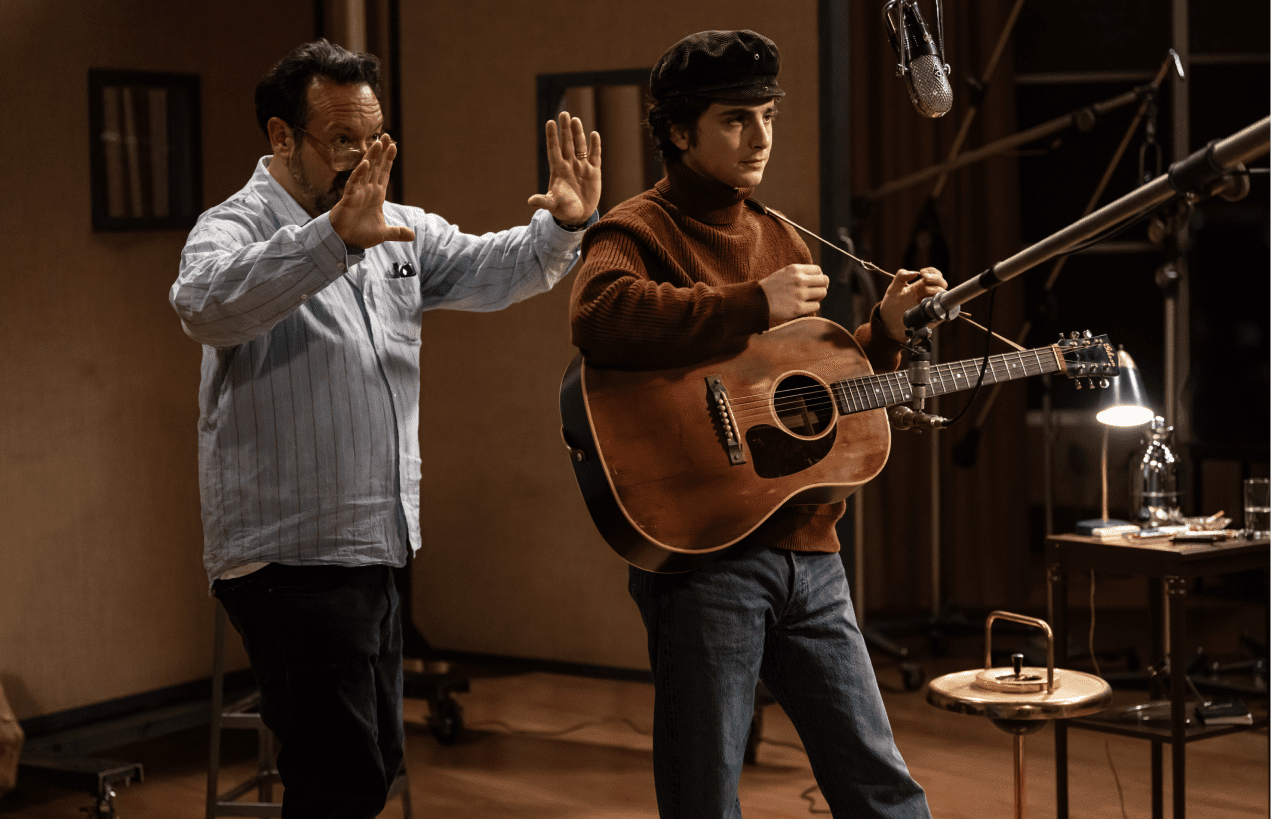

Chapter7

Location & Set Build

Columbia

Records

Studio A is revered among Dylan enthusiasts as the site where he recorded his first six albums.

This historic studio also hosted legends like Aretha Franklin, Miles Davis, Barbra Streisand, and Simon & Garfunkel.

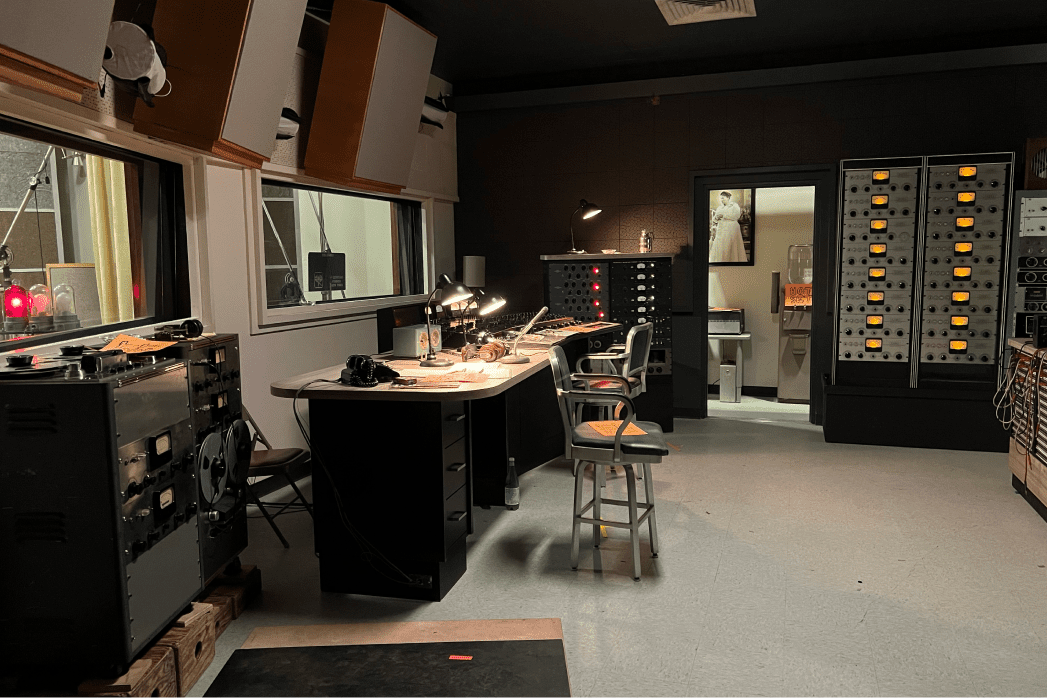

We challenged ourselves to forensically reconstruct “Studio A,” analyzing over 1,500 photographs taken by various photographers who documented its sessions. The set was built as a 1:1 recreation, replicating every possible detail, from the custom sound-mixing board to the baffle walls, microphones, speakers, music stands, pianos, and organs.

The Columbia mixing board was meticulously recreated by “Sound City” in Vermont as a practical prop, complete with functional VU needles connected to the studio microphones. Every vintage microphone and speaker was operational, allowing the production to record Dylan’s performances live, just as they would have been captured in the 1960s.

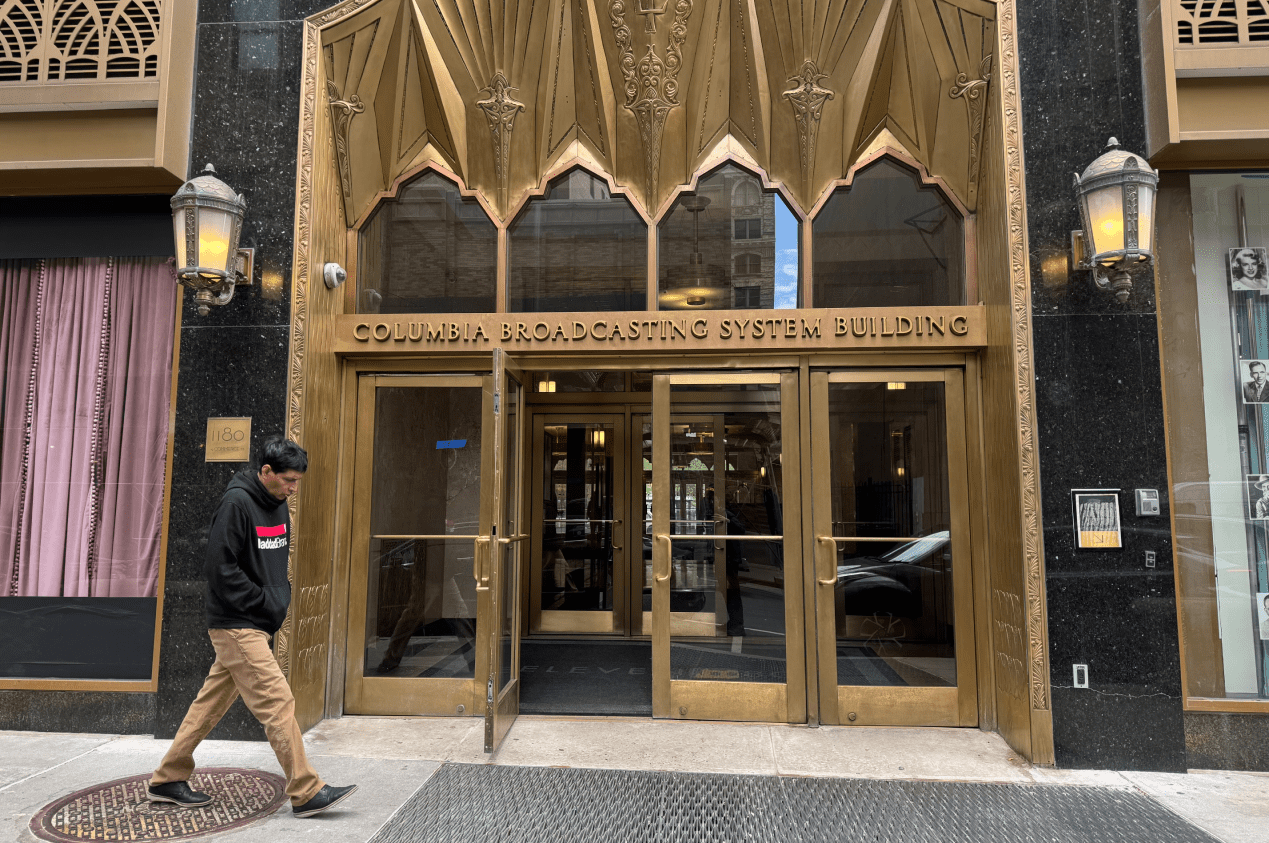

Lobby scenes were filmed in an art deco skyscraper at 1180 Commerce Street in Newark, which convincingly doubled as Midtown Manhattan.

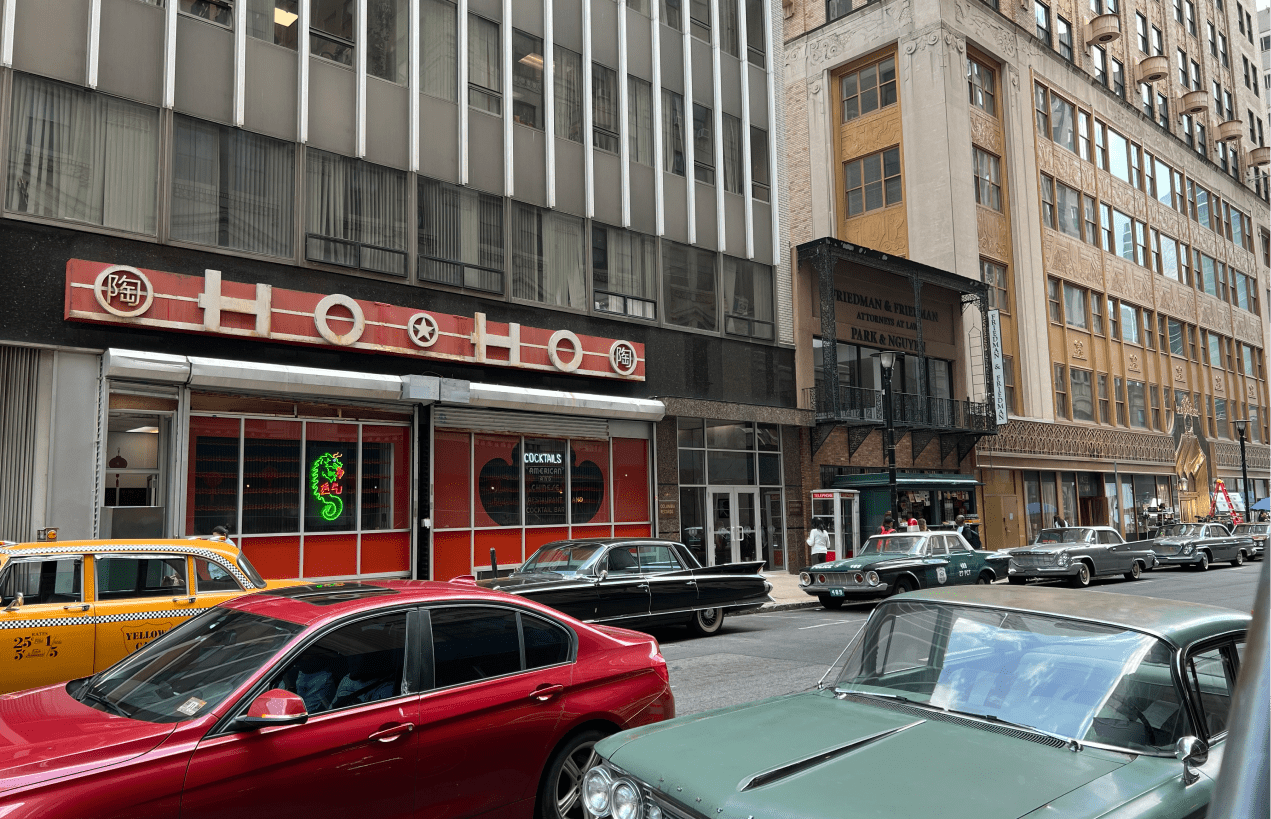

The street-level atmosphere was also enhanced with era-specific touches. Window displays featured the latest albums of the time, including a prop version of Dylan’s “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.” Adjacent to the set, we recreated the façade of the Hi-Ho Chinese Restaurant, a real establishment that once stood next to CBS/Columbia.

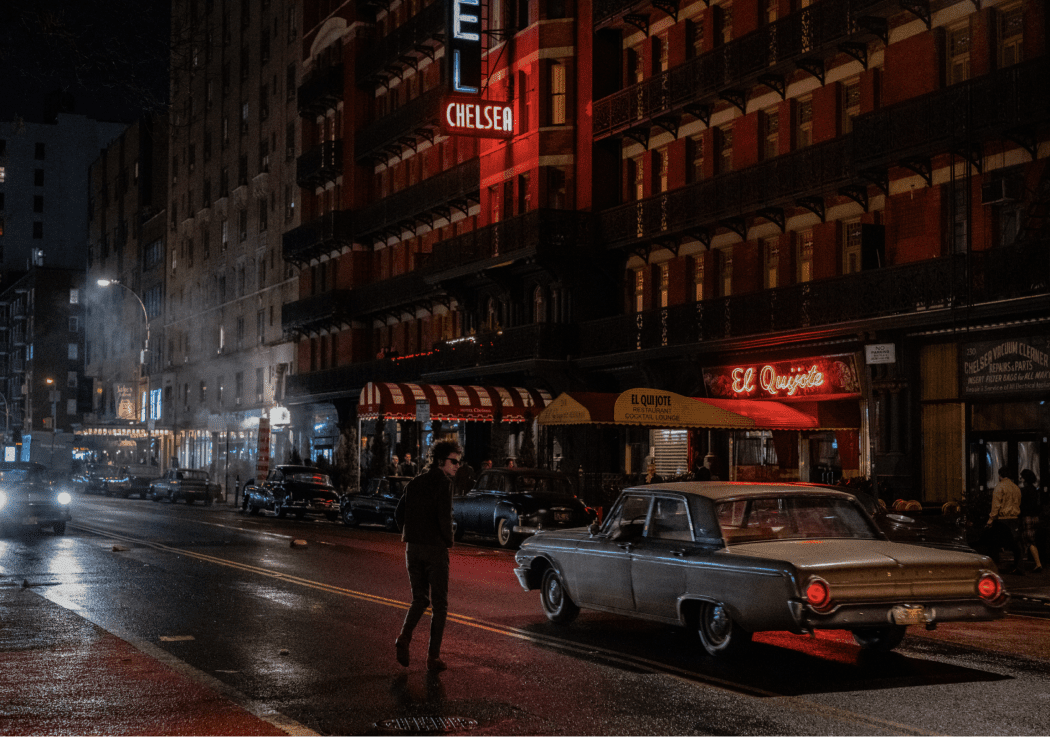

Chapter8

Location & Set Build

Chelsea

Hotel

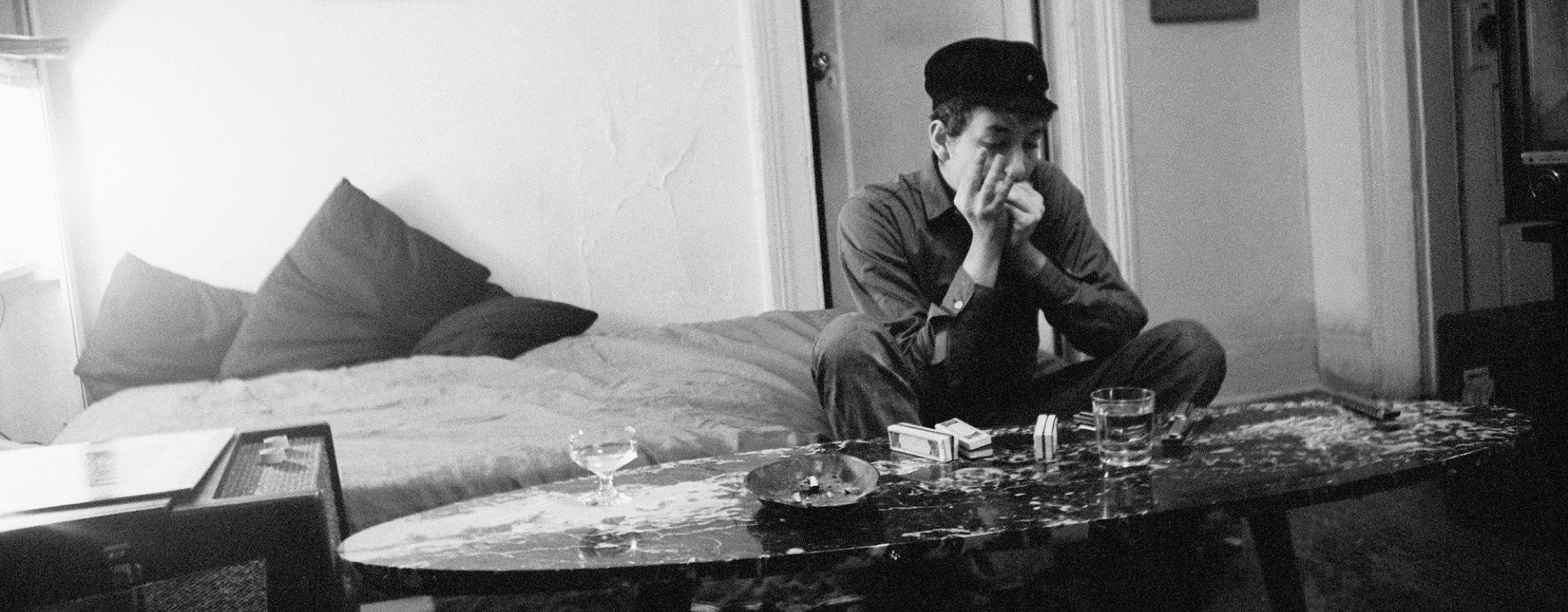

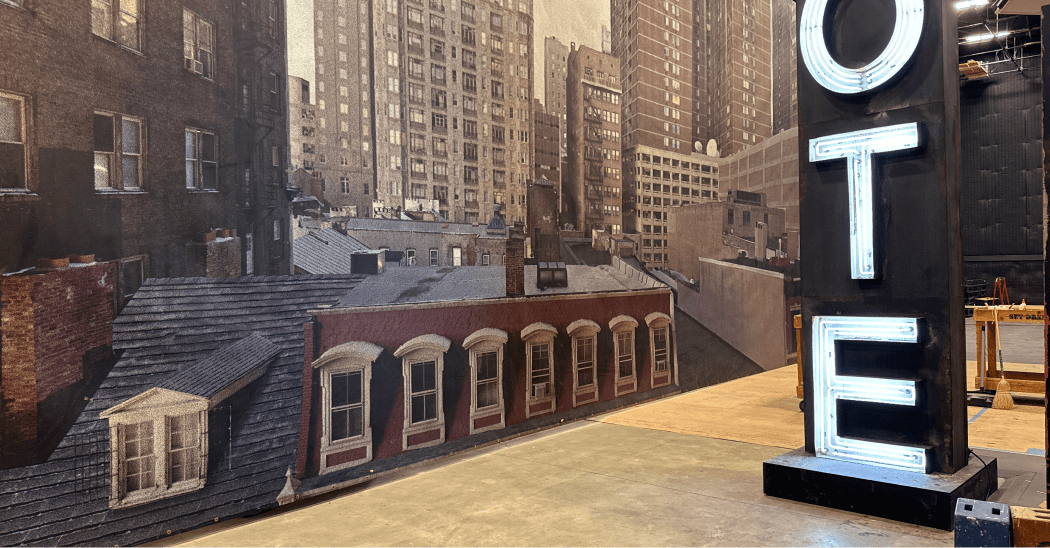

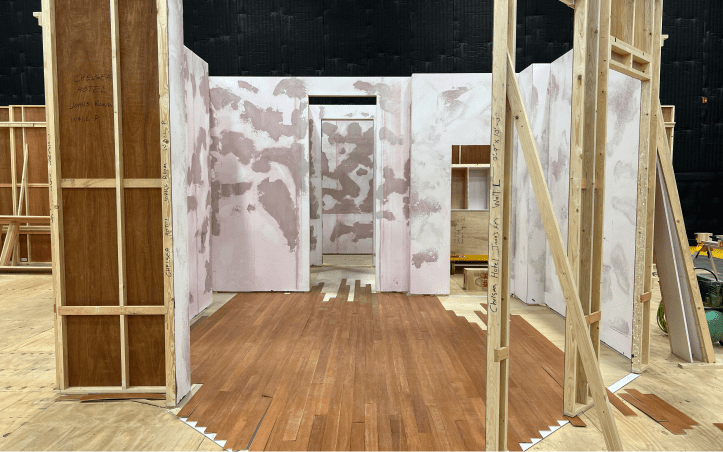

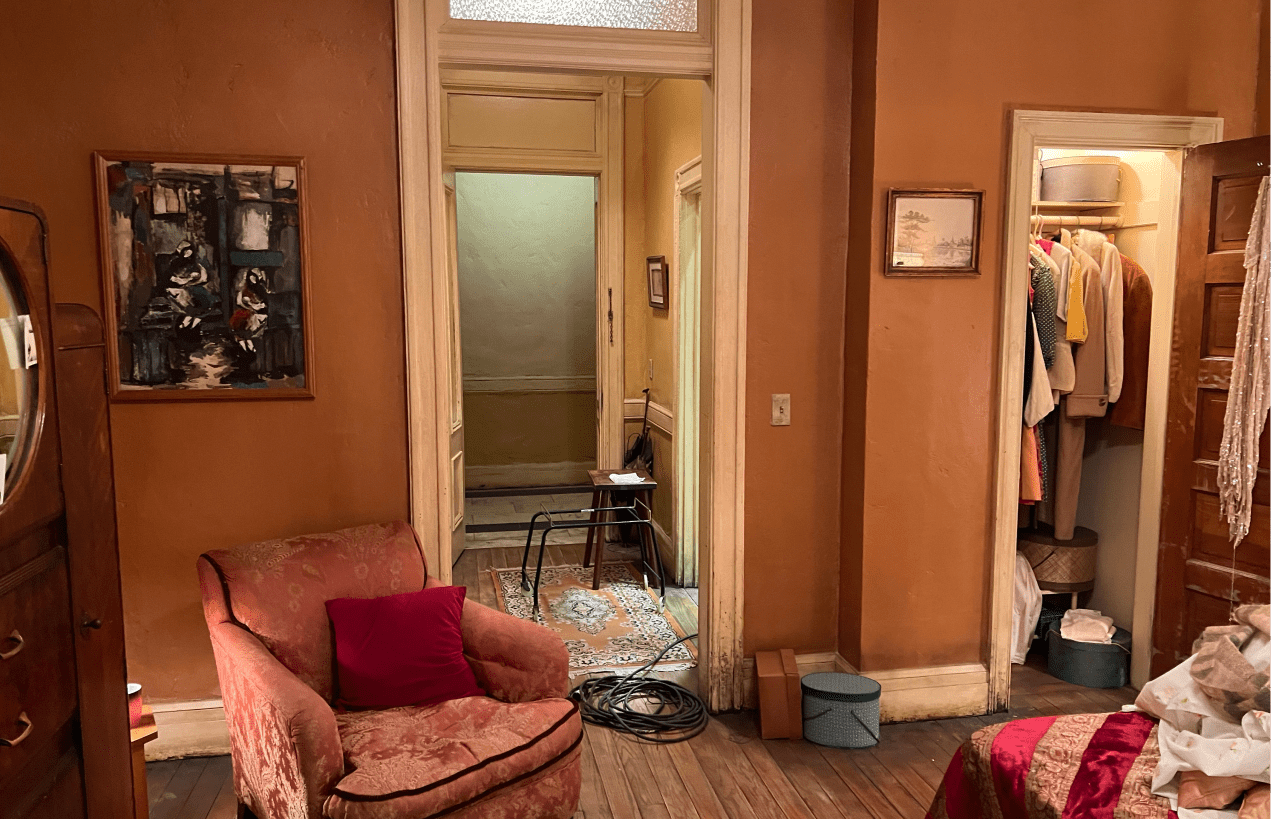

We had the great fortune of filming the exterior of the well-preserved Hotel Chelsea in NYC, while Joan Baez’s room and its connecting hallway were constructed on stage.

The Chelsea Hotel of the early 1960s—fondly nicknamed the “Dowager of 23rd Street”—was built on stage with a neon HOTEL sign mounted to a bay window overlooking a rented New York cityscape backing. To suit the camera angles and framing, we fabricated only the letters “OTE” in period-correct neon, as the window naturally cropped the sign.

This hotel—with its layers of caked-on plaster and nicotine-stained patina—captured the gritty, bohemian atmosphere that made the Chelsea a haven for artists, musicians, and poets like Dylan Thomas, Arthur Miller, Leonard Cohen, and Andy Warhol. They all found inspiration within its storied walls—a legacy we sought to honor in every detail.

“Did you actually come here to make me watch you write a song at 1 a-m? Or were you just too scared to be alone?”

Joan Baez

Chapter9

Location & Set Build

Viking

Motel

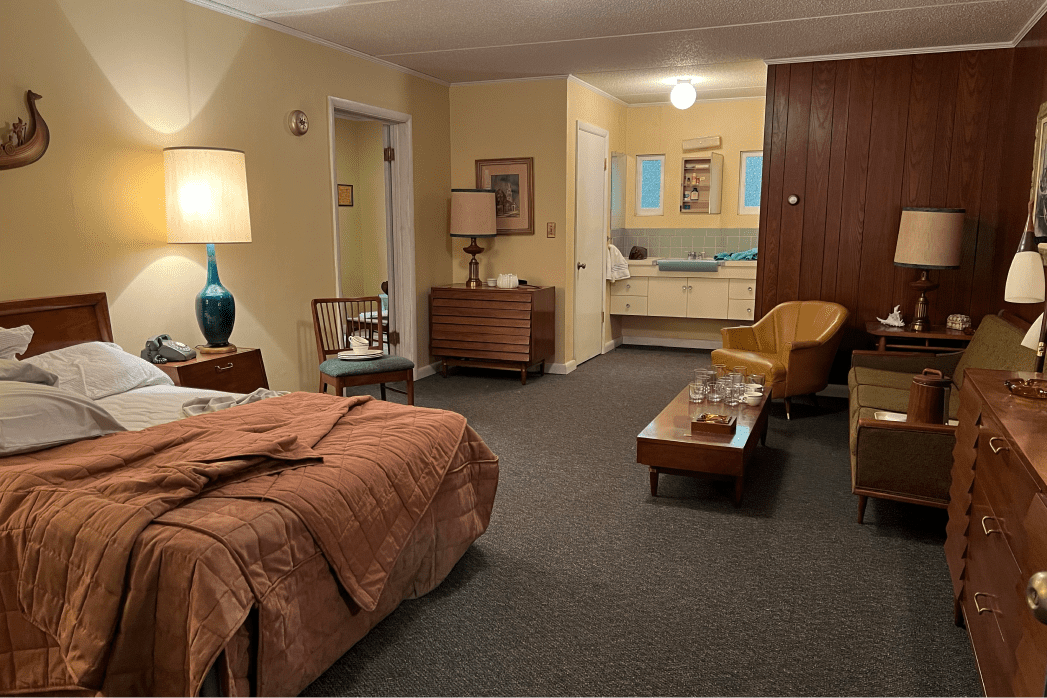

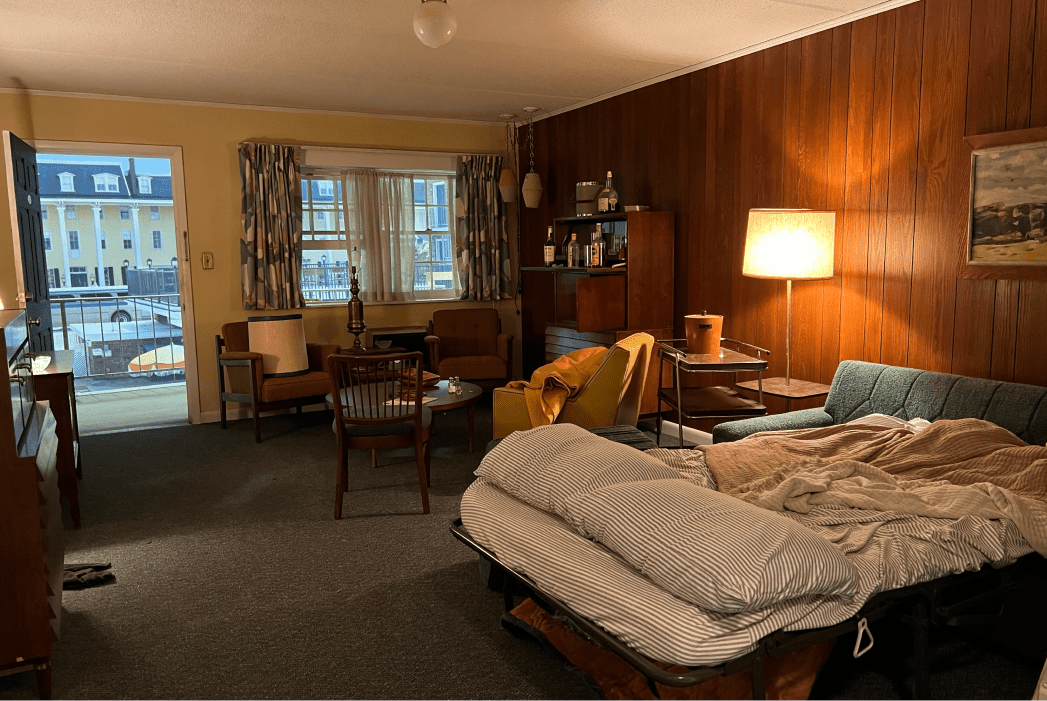

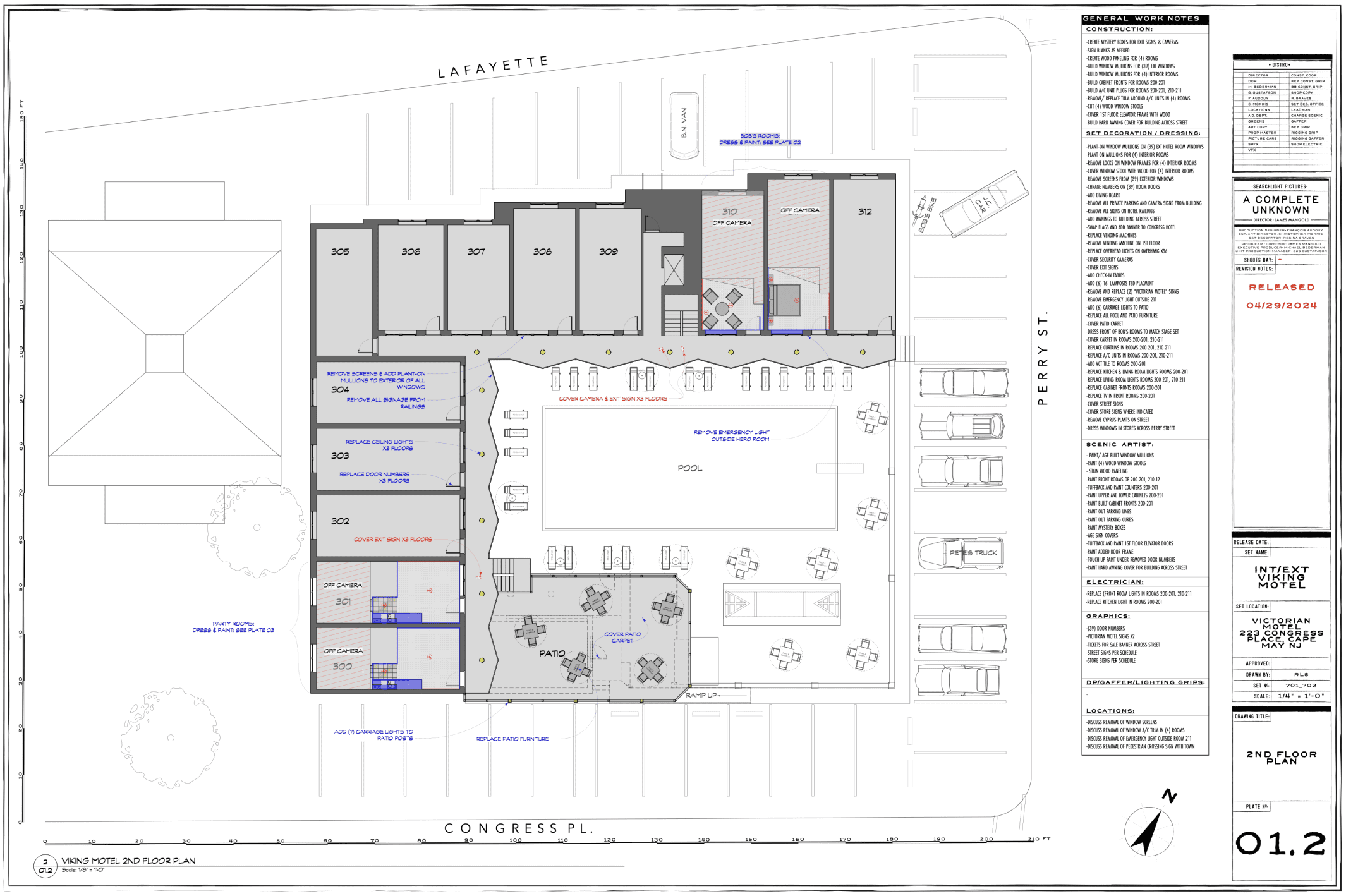

” style=”font-weight: 400; white-space: normal;”>Located in downtown Cape May, New Jersey, the four-story Victorian Motel underwent extensive dressing to evoke the mid-century aesthetic of the Viking Hotel. Key elements included the addition of 65 vintage pendant light fixtures, and new window mullions.

Four interior rooms were dressed and period patio furniture and vintage practical lighting were added to the three-floor hotel that overlooked the bucolic downtown.

Dylan’s suite at the Viking Motel was constructed on a soundstage, featuring a custom backing printed by Rosco. The backing originated from a shoot in Cape May but was digitally enhanced by the art department in Blender 3D. They incorporated 1960s vehicles, signage, and other period dressing to complete the illusion of a bygone era.

“Then you came along, Bobby.. and you brought a shovel. We just had teaspoons. But you brought a shovel.”

Pete Seeger

Chapter10

Location

Monterey & Newport

Folk Festivals

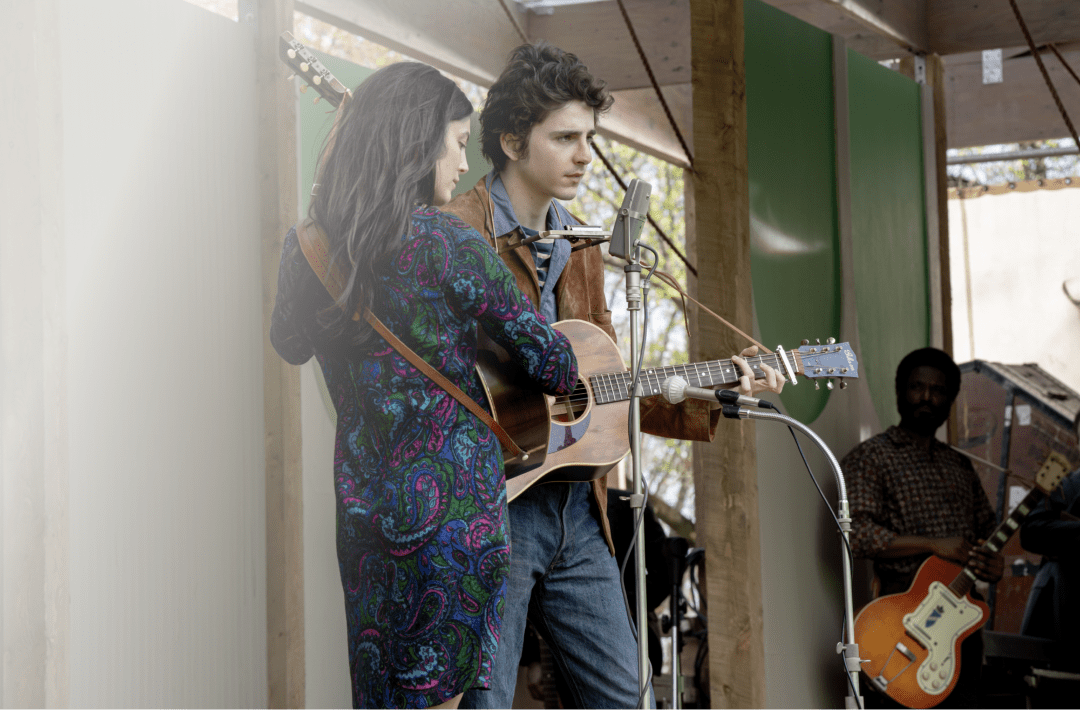

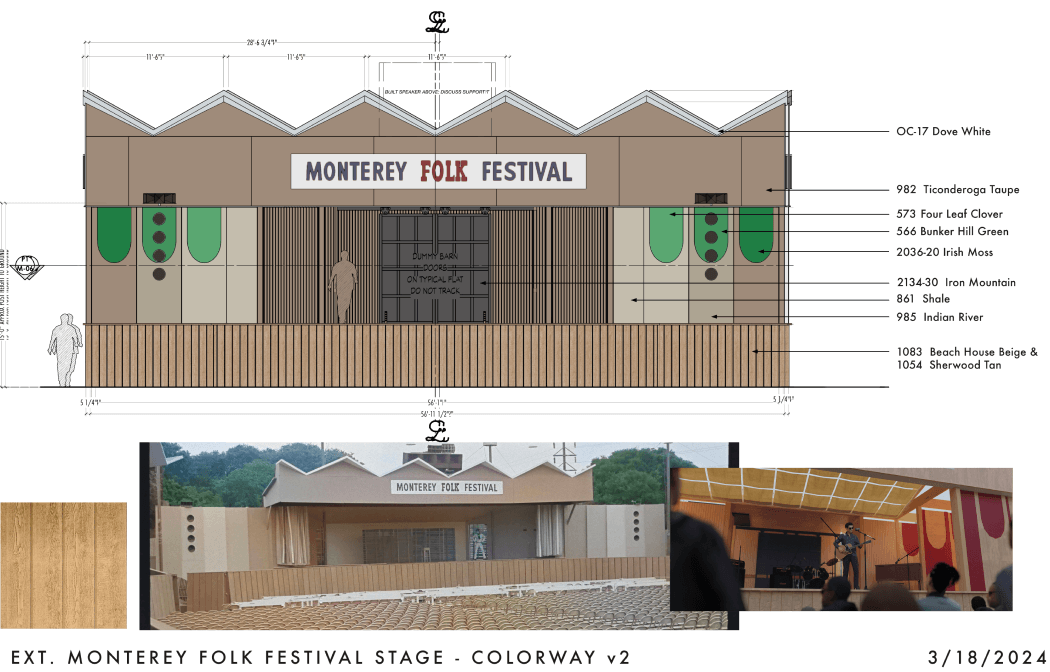

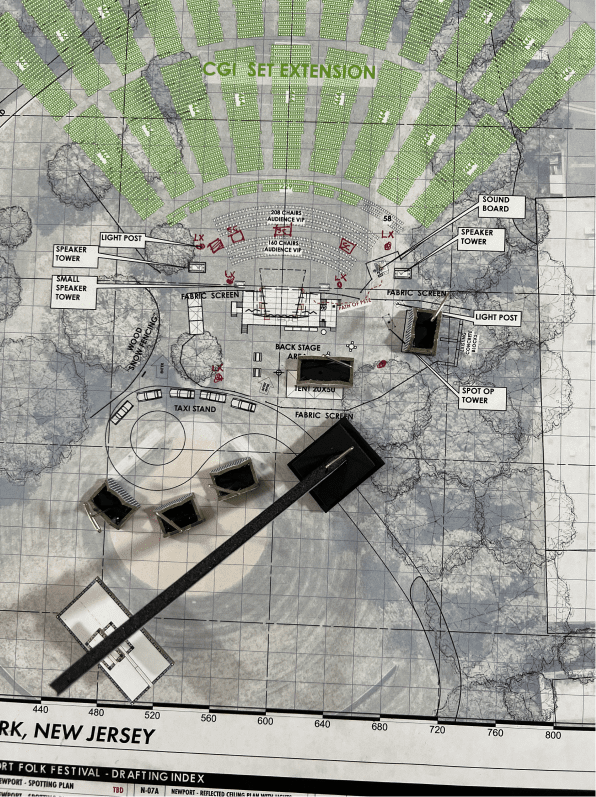

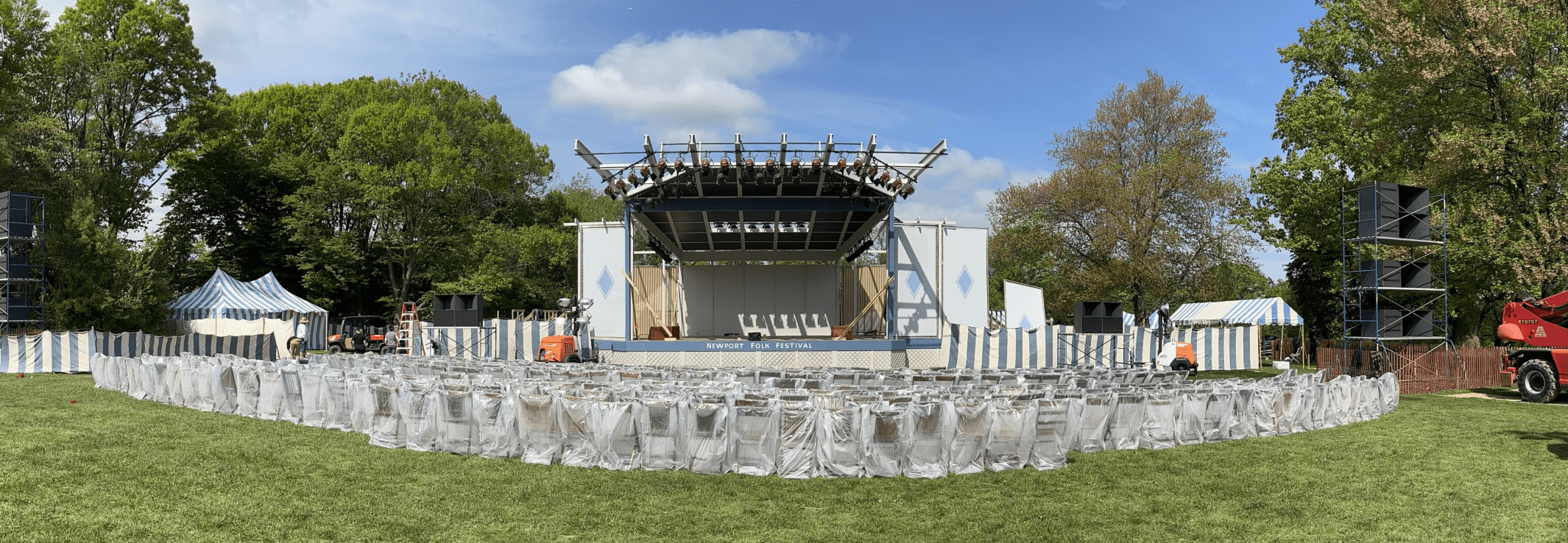

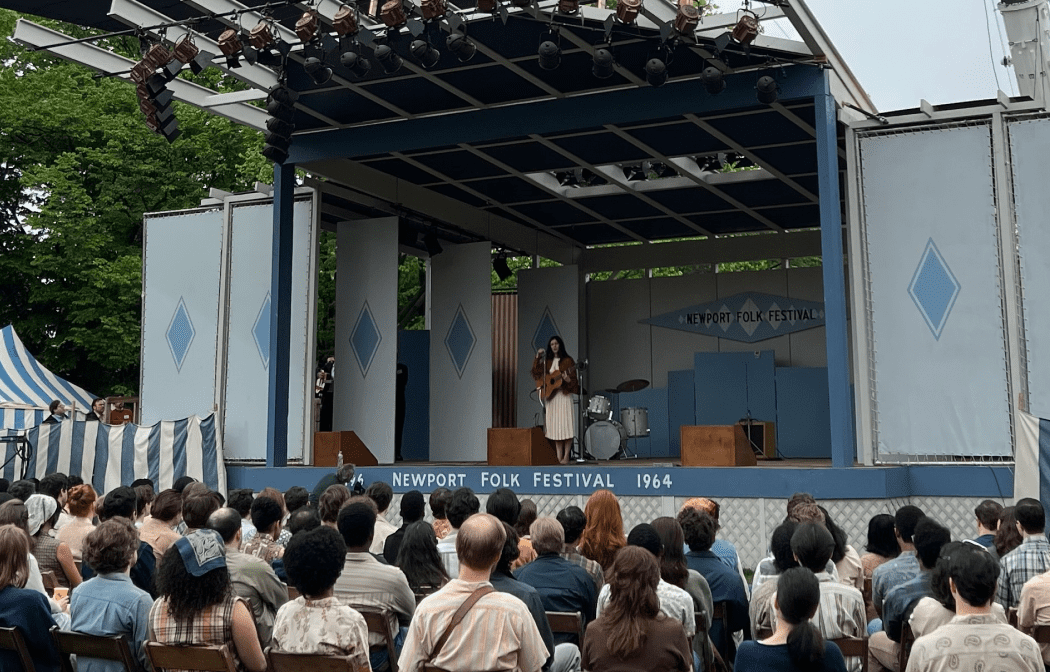

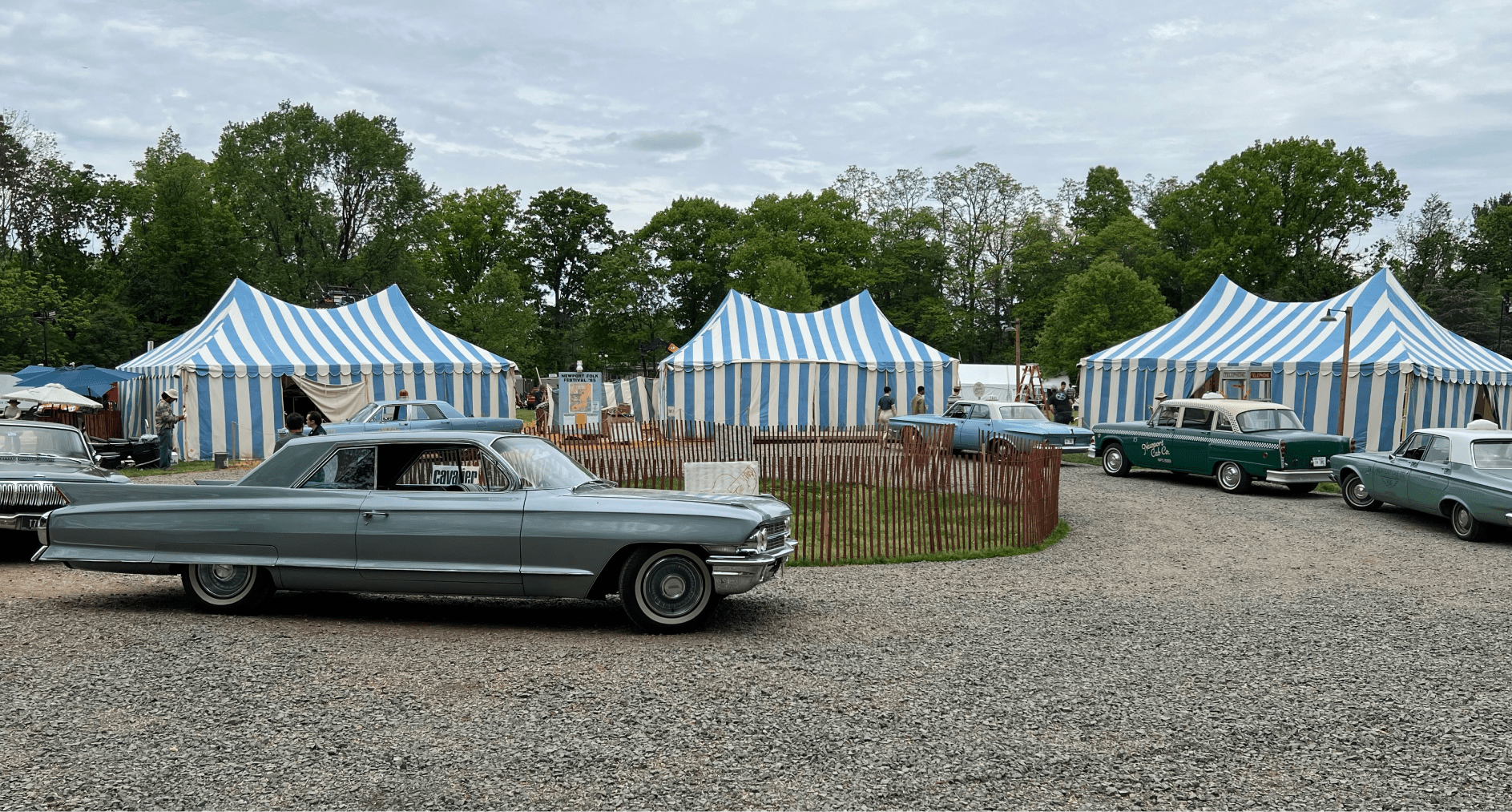

These sets were among the most extensive, encompassing the 1963 Monterey Folk Festival and the 1964 and 1965 Newport Folk Festivals, including Dylan’s iconic moment of “going electric,” which stunned his fans and marked a turning point in music history.

The Monterey fairgrounds were built in a community park with a stage and retractable old canvas ceiling, accurately depicting the festival’s atmosphere.

The stage was redressed over two weeks to depict the Newport Folk Festival. Artificial turf was laid down over the immediate area surrounding the stage to mask the muddy paths that were byproducts of our heavy equipment required by the construction and grip teams.

Newport Folk Festival

“There’s an evocative sense of history in the outdoor festival scenes are vibrant gathering places with very little separating the artists from the audiences, utterly unlike the commercialized Coachellas of today.”

David Rooney

The Hollywood Reporter

Lauren Sandoval, our art researcher, unearthed invaluable reference material from the 1964 and 1965 Newport Folk Festivals. This research, combined with footage from Murray Lerner’s documentary Festival (1963–1966), provided a springboard for the set design effort.

While grounded in historical accuracy, we enhanced the backstage and wing areas with additional layers to support the numerous transitional scenes that unfold between the stage and its surroundings, adding depth to the narrative.

The set decoration team sourced 1,000 wooden folding chairs to populate the festival grounds, while VFX extended the crowd far beyond the 200 extras available on set.

For the night scenes, the stage was repainted one shade darker, an effort that Cinematographer Phedon Papamichael appreciated as it allowed greater control over exposure.

A logistical challenge arose with the need for a 300-ton crane positioned behind the stage to provide consistent shade and lighting continuity. Careful planning ensured its placement remained invisible to the camera, maintaining authenticity in every shot.

“Show me the country where bombs had to fall, Show me the ruins of buildings once so tall, And I’ll show you a young land with so many reasons why. There but for fortune, go you or go I — you and I.”

Joan Baez

“There But For Fortune”

One particularly dynamic moment involved a scene where Sylvie Russo (played by Elle Fanning) rushes to a waiting taxi behind the stage. Initially modest in scope, this scene was expanded at the eleventh hour, prompting a rapid build of a full taxi-stand traffic circle. This area was enveloped by artist tents and dressed with period-appropriate Newport taxis, creating a richly detailed backdrop for this dramatic moment in the story.

I am so grateful to my extraordinary team who brought it to life with such passion and precision. Supervising Art Director Chris Morris was an incredible partner in overseeing the vision and ensuring every detail aligned seamlessly. My graphic designers—Will Hopper, Kerri Mahoney, and Ashley Waldron—poured their hearts into crafting graphics that added authenticity and richness. Kristian Llana’s stunning concept illustrations guided our creative journey, while Assistant Art Directors Benjamin Cox, Rebecca Lord-Surratt, and Peter Dorsey worked tirelessly to execute the many facets of our layered world.

Researcher Lauren Sandoval worked for over a year sourcing thousands of images that served as our inspiration. Thank you!

Set Decorator Regina Graves deserves special recognition for her unmatched artistry and keen eye for detail. Property Master Michael Jortner’s contributions went above and beyond—sourcing not only every prop and period instrument but also the majority of the picture cars. Charge Scenic Alex Gorodetsky and his talented paint team added depth and character to our sets with their textured artistry, layering each space with history and life.

The art department wouldn’t have functioned with the coordination of Leonard Bruno and support of our assistants Lucien Aleman, Jaime Mejia and Louis Medrano.

To the entire art crew: your dedication, creativity, and passion made this world come alive. I’m profoundly grateful to each of you for making this journey unforgettable.

Art Department Credits

- Supervising Art Director

- Christopher J. Morris

- art dept. coordinator

- Leonard Bruno

- Set Decorator

- Regina Graves

- Assistant Art Directors

- Benjamin Cox

- Rebecca Lord-Surratt

- Peter Dorsey

- Concept Illustrators

- Kristian Llana

- Matthew Sama

- Graphic Designers

- Will Hopper

- Kerri Mahoney

- Ashley Waldron

- Storyboard Artist

- Gabriel Hardman

- Researcher

- Lauren Sandoval